- The EU and US have agreed a deal which features a 15% headline US tariff rate (with some exemptions) and an EU commitment to increase investment and energy purchases. Details are still thin at this point but it’s clear that the EU has ultimately swallowed an unbalanced outcome to reduce downside risks. The deal itself looks bearable (we estimate the GDP impact at ~0.2%) and the hope in Brussels will be to move on from trade policy uncertainty. Euro area growth conditions are set to brighten, provided that this proves to be a stable equilibrium.

The EU has swallowed an unbalanced outcome

Pragmatism over principle

A US-EU trade deal has been reached with a headline 15% US tariff rate and EU investment commitments. Details remain thin at this point but there are plenty of parallels with the US-Japan trade deal. This is what we know from yesterday’s press announcement and a subsequent statement from von der Leyen:

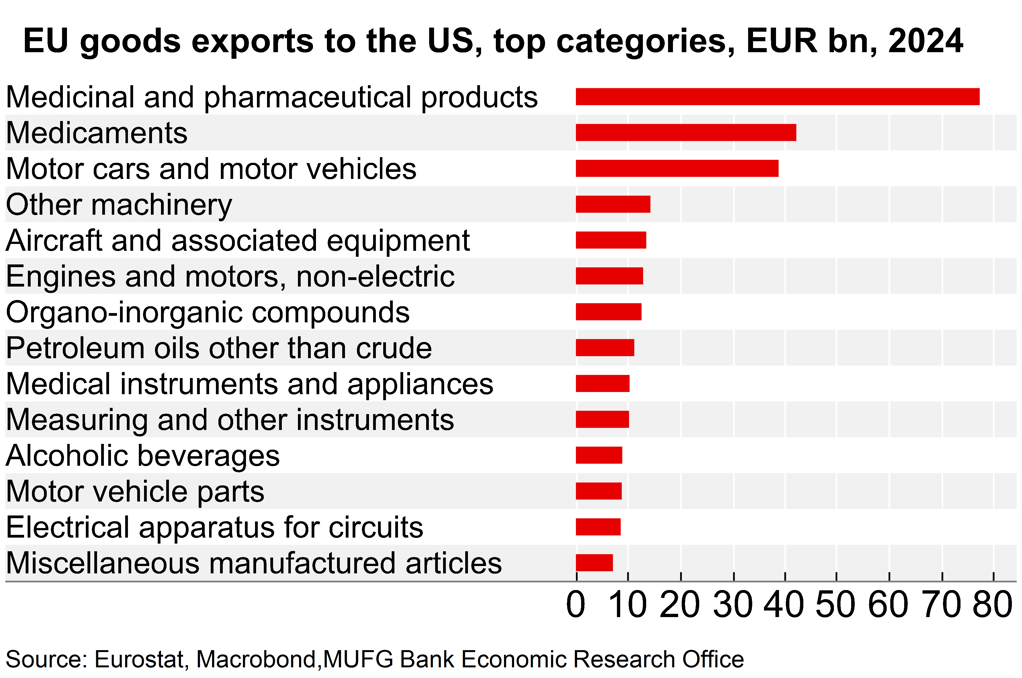

- A 15% US tariff rate on most EU goods, which replaces most previous rates (rather than being stacked on top). This includes cars, semiconductors and pharmaceutical products.

- ‘Zero-for-zero’ tariffs on certain “strategic” products (aircraft and parts, some chemicals, some generic drugs, semiconductor equipment, certain agricultural products, natural resources and critical raw materials).

- Steel and aluminium remain subject to a 50% tariff, but with an aim (no time frame at this stage) to move to a quota system.

- An EU commitment to increase its investment in the US by 600bn USD, increase military purchases by an unspecified amount, and spend 250bn/year on US energy imports.

Looking at that, it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that the EU has accepted an outcome which is both tilted in the US administration’s favour and much less detailed than any agreement which would normally be countenanced by Brussels. Make no mistake, this is clearly a victory for pragmatism over principle – the EU has opted to deviate from its normal approach to trade talks in order to prioritise certainty and reduce downside risks.

Yet the apparent 10% US tariff rate floor (which was applied to UK goods under the first agreement) always seemed likely to be out of reach for the EU given its large goods trade surplus (200bn EUR) with the US. A 15% rate may have been as good as it could get for the EU. There is also no indication that the EU has made any regulatory concessions (e.g. product standards) as part of the deal, which is likely to have been a red line for most in Brussels.

It’s hard to comment on the commitments for investment, defence and energy given the lack of detail around any actual mechanisms at this stage – but the vagueness and longer-term nature of this part of the deal might suggest scope for slippage.

Ultimately, we see this as a good deal for the EU, in the circumstances. We estimate that 15% tariffs would equate to a hit of around 0.2% GDP – not ideal, but bearable. From a European perspective the hope will be to move on now and leave trade uncertainty behind. That’s far from given. Trump could plausibly reach for the tariff lever again if there’s a sense that Europe is not following through on its commitments to increase defence spending or energy imports, for example. The EU has never seemed especially likely to follow through with its various officially-communicated options for countermeasures (opting instead for a stance of ‘strategic patience’). That stance would certainly be harder to maintain if this deal, apparently negotiated in good faith, were to collapse.

Meanwhile, this deal still needs to be ratified, including in the European parliament. The US administration is also conducting sector-specific tariff reviews (while also contending with domestic legal challenges around universal rates). In short, there are still plenty of sources of uncertainty. The risk of tariff escalation will probably continue to exert at least some drag on business sentiment.

The wider shift in global trade policy also remains hard to predict. Now that we are approaching a more stable equilibrium on US policy, it seems that the US average tariff rate could plausibly settle at the highest mark since the early 1900s. The ramifications of that for the global economy are unclear. It was interesting to hear Lagarde say last week that there will “probably be some bottleneck issues as a result of the trade disruption”. We haven’t seen any sign of that yet, nor of any meaningful trade diversion from Asian exporters away from the US and towards Europe, but both could plausibly disrupt the economy’s recovery.

Clarity (and hopefully stability) on US policy around pharma and cars is welcome

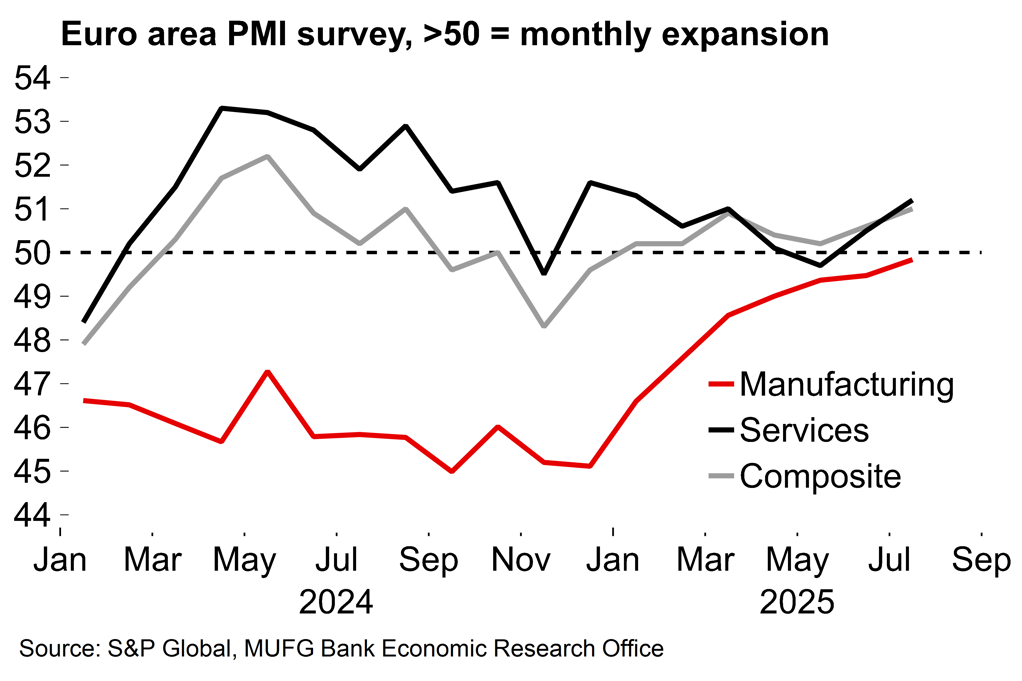

There is scope for further improvement in euro area business sentiment

A better platform for growth

While risks remain, this is a more benign outcome than we expected. Our central scenario had been for US tariffs to settle at 20% after a bumpy negotiation process. We will revise up our GDP forecast for the euro area (0.9% in 2025). Our next full update will be released later this month, but for now we are pencilling in a figure of 1.2%.

Even before this increase in trade policy clarity there have been signs of stronger underlying resilience with the latest industrial production numbers suggesting that the Q2 slowdown may not be as pronounced as initially feared. It’s also worth flagging that there was a downward revision to the volatile Irish growth numbers earlier this month (now estimated at 7.4% Q/Q in Q1, from 9.7% in the previous estimate). That suggests a possible downward revision of around 0.1pp to the Q1 euro area aggregate (0.6%), but also less payback in Q2 than expected. The first estimate will be released on Wednesday. We are tracking a figure of 0.1% Q/Q for Q2 euro area growth.

Looking ahead, last week’s survey data pointed to better momentum at the start of H2, consistent with moderate growth. Indeed, at last week’s ECB meeting (our take here), Lagarde sounded notably upbeat on the economy’s underlying health over the medium term. Combined with the significant German fiscal stimulus coming down the track this looks like a good platform for growth, even if yesterday’s deal itself is clearly unbalanced away from the EU.