The Bank of England became the first major central bank to raise interest rates since the start of the pandemic. It seems a bold call given the uncertainty around the Omicron variant but can be warranted given decade-high inflation and an increasingly tight labour market.

Surging inflation and a tighter labour market prompt action

After its unexpected inaction in November, the Bank of England increased rates from 0.10% to 0.25% yesterday with a near unanimous 8-1 vote. The decision to pull the trigger and raise rates now this time was also surprising given the uncertainty around the spread of the Omicron variant.

We had gripes around the communication around the last meeting but it seemed reasonable in November to wait given uncertainty around the labour market following the end of the furlough scheme on 30 September. The MPC could easily have pointed to Omicron uncertainty to warrant holding fire once again at this meeting.

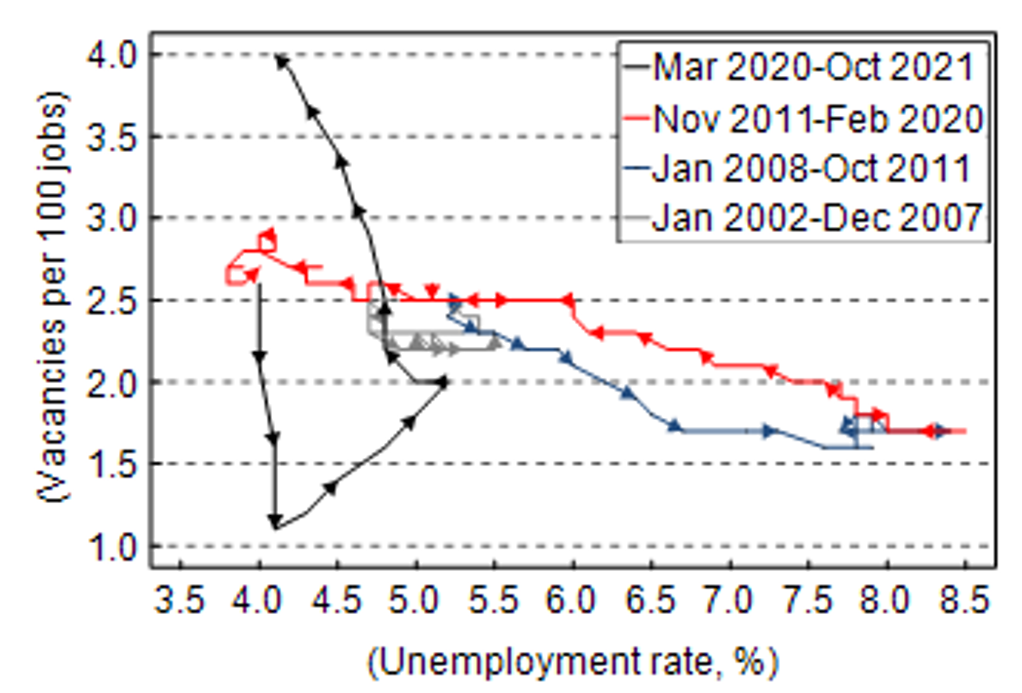

As it turns out, there was no discernible post-furlough scheme damage to the labour market. In fact, it may have been that unexpected tightness in the latest jobs figures forced the BoE into action. Early estimates released on Tuesday suggest that there was an increase of 257k in the number of payrolled employees in November leaving the total number now 1.5% above the February 2020 level. Median monthly pay increased by 4.7% Y/Y, and this is probably close to the true ‘underlying’ rate: the ONS has suggested that most temporary pandemic-related distortions have now worked their way out of the latest growth rates.

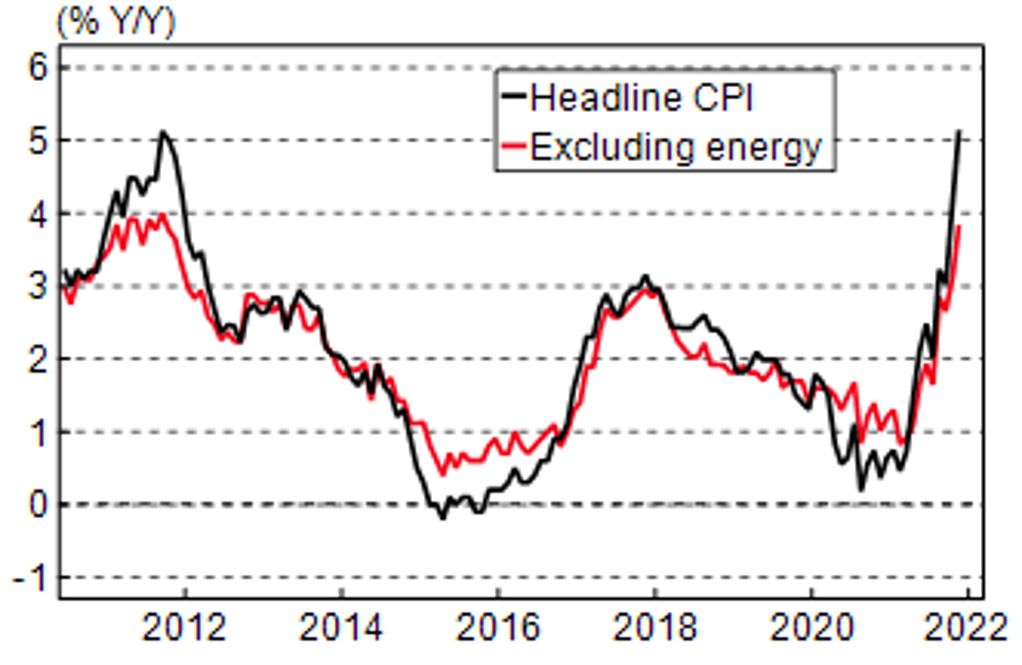

With CPI inflation reaching 5.1% in November, up from 4.2% to the highest rate in a decade, the MPC judged that monetary policy tightening is necessary to try to limit these pay pressures from becoming more persistent. The BoE now expects 5%+ inflation to continue through the winter before a peak of around 6% is reached in April (when the domestic energy price cap is set to be increased).

At the same time, the emergence of Omicron could lead to higher inflation for longer. Global supply bottlenecks had been showing some signs of easing but these could increase again if Omicron leads to factory closures and worker absence. There could also be a rotation from services consumption (such as bars and restaurants) back towards goods, which are more sensitive to supply-chain problems and have shown considerably higher rates of inflation in recent months.

THE LABOUR MARKET HAS QUICKLY TIGHTENED

Source: ONS, MUFG Bank Economic Research Office

INFLATION AT A DECADE HIGH

Source: ONS, MUFG Bank Economic Research Office

A brave move as Omicron spreads rapidly

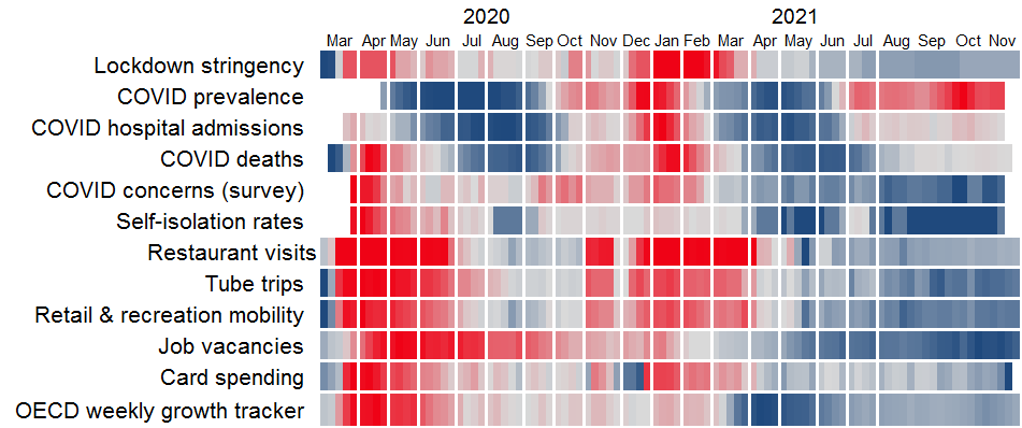

The move can be justified but it certainly seems a brave call from the Bank of England to raise rates a day after the country’s COVID caseload reached a record high. The MPC itself noted that the spread of the Omicron variant would “unambiguously slow economic activity”. So far, the UK government, which is facing various political pressures, has shown its reluctance to tighten restrictions beyond guidance on mask wearing and working from home. The number of hospitalisations remains the key driver for any further lockdown measures. Despite good vaccination coverage, admissions could certainly rise given the apparent transmissibility of the new variant even if it does prove to be more benign than Delta. Higher caseloads may also mean higher staff absence which could put the healthcare system under extra strain this winter. To our minds it would be no surprise to see further restrictions implemented after Christmas.

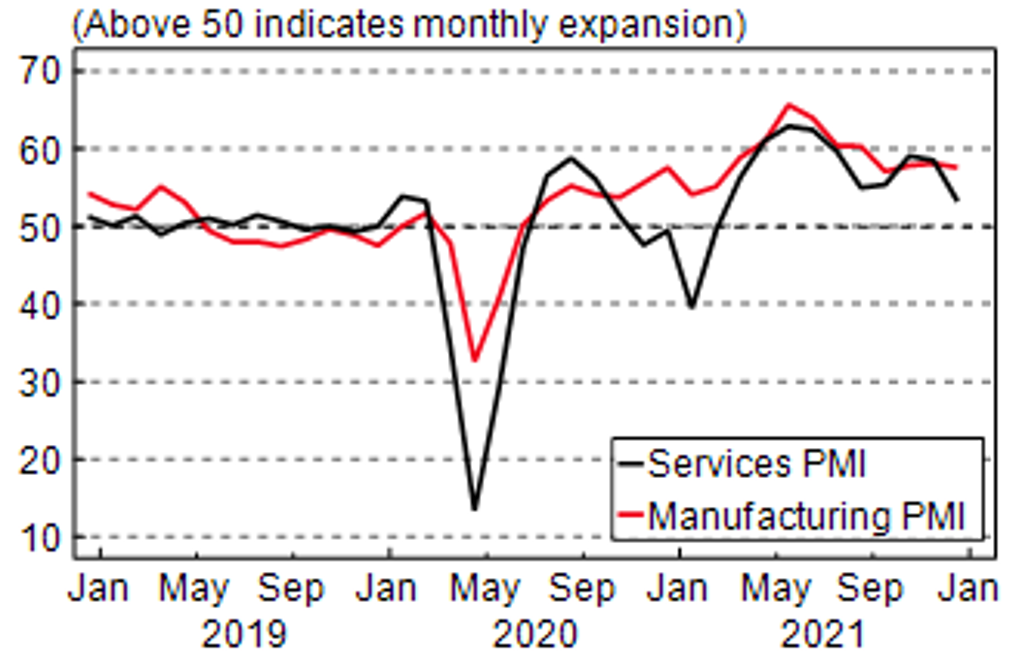

While the government may not introduce tighter measures, it still seems likely that individuals will voluntarily limit social contact given the spread of the virus and so customer-facing industries are set to face another tough winter. There was already a pronounced slowdown already in this month’s services PMI, which fell to the lowest mark since February.

UK WEEKLY COVID TRACKER

Red = worst in range, blue = best.

Source: Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Google, ONS, OECD, NHS, UK Department for Transport, OpenTable, MUFG Bank ERO

Meanwhile, there is likely to be less support for the economy – the government has not yet suggested any extra help for the hospitality sector ahead of what looks to be another challenging period, nor is the furlough scheme likely to be reintroduced in the absence of tighter national restrictions. The BoE’s rate hike, while small, won’t help either. The majority of loans to businesses are on floating rates and so many firms will see their costs increase at the same time as takings are falling.

Against that background, we have recently revised down our growth prospects for the UK in 2022 from 5.2% to 4.5%. But the good news is that the UK economy has shown that it can bounce back quickly from any restrictions. Monthly GDP is now just 0.5% below its pre-pandemic level and the macroeconomic impact of COVID waves has diminished each time as measures have become more targeted and households and businesses have learnt how to adjust. We see no reason at this stage to assume that another round of COVID measures would increase the degree of economic scarring over the long-term, even if GDP were to slip back again due to any new restrictions.

PRESSURE ON HOSPITALS MAY INCREASE

Source: ONS, PHE, MUFG Bank Economic Research Office

WANING BUSINESS CONFIDENCE

Source: IHS Markit, MUFG Bank Economic Research Office

Further hikes to come if pandemic risks subside

This week the IMF warned the BoE against “inaction bias”. That fear can be put to bed: yesterday’s decision to hike rates despite the Omicron uncertainty is a clear indication that the BoE won’t actively be looking for excuses to sit on its hands as we’ve often seen from central banks in the past. Indeed, it suggests a perceived urgency to tighten policy. The UK government’s chief medical adviser has said that the Omicron wave “may come down faster than previous peaks”. So a back-to-back move from the BoE with another hike at the next meeting in February seems a real possibility, despite the COVID-related gloom on the immediate horizon.

The IMF also suggested that “careful communication would be needed to lay the groundwork with markets for potentially more frequent policy moves”. But even if the added Omicron uncertainty were to quickly clear, it seems fair to question whether rate normalisation will be smooth and predictable after two consecutive surprises from the BoE (one MPC member said only two weeks ago that it was “premature” to talk about rate hikes but then voted to hike yesterday). As yet there hasn’t been much guidance about the extent of a rate hike cycle. It is plausible that the BoE could hike again in short order to 0.50%, the point at which passive balance sheet reduction would come into play, before moving to a “wait-and-see” stance. Inflation could then normalise quite quickly in H2 2022 if supply congestion clears and reinforces downward pressure on headline CPI from base effects and reduce the scope for further moves.

But another hike to 0.50% would leave rates 25bp below the pre-pandemic mark and still on a very accommodative setting. With inflation likely to remain above 5% through most of H1 next year, three 25bp hikes in 2022 certainly can’t be ruled out. This would take Bank Rate to the 1% mark at which the BoE would consider active balance sheet reduction (see here) – and so might be the extent of the hiking cycle.