- Headline UK inflation came in at 3.8% in September, 0.2pp below both the BoE’s projection and market consensus. Upward pressure from energy base effects were offset by markedly lower food inflation and more gradual progress on underlying services inflation. Labour market slack and cooling pay pressures support the view that inflation has now peaked.

- The CPI release bolsters our call for a December rate cut with hawkish concerns around food inflation now looking less valid. The November meeting may also be tighter than expected, especially if the PMIs and/or retail sales were to disappoint later this week, but we suspect that wavering MPC members will want to see further evidence of disinflation progress as well as clarity on UK fiscal policy before voting for a cut.

- On the Budget, the need for consolidation remains. But there have been various noises from the government suggesting that lessons have been learnt from previous policy missteps. The apparent focus on avoiding distortive/inflationary measures is welcome. A relatively market-friendly Budget outcome combined with increased expectations around BoE cuts would be supportive for UK sentiment into 2026.

Downside inflation surprise leaves the door wide open for more BoE easing this year

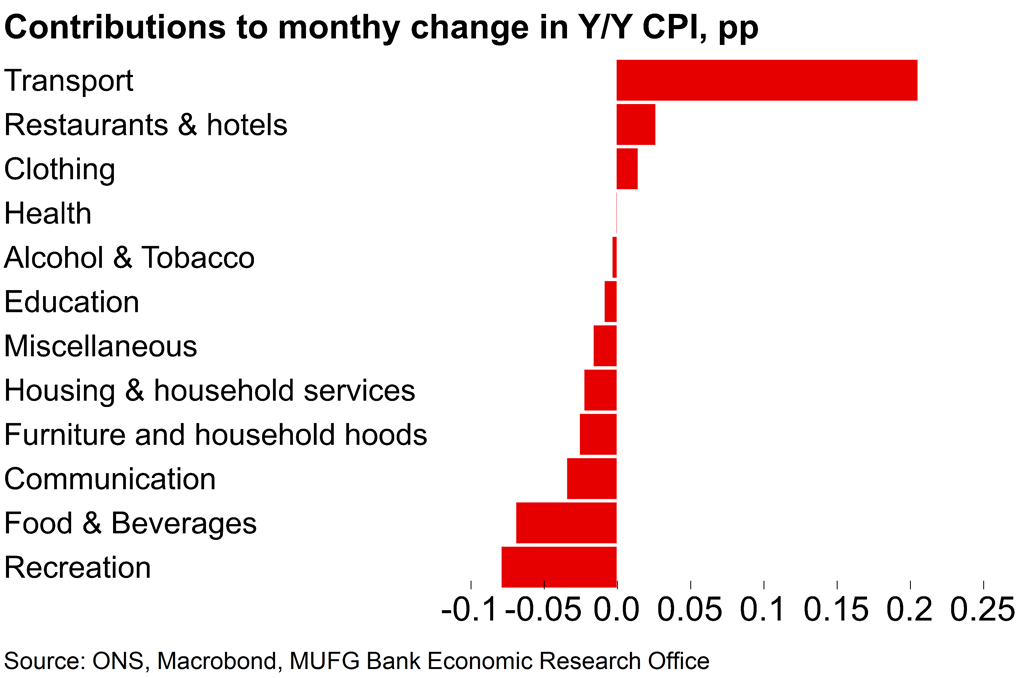

Headline UK inflation remained unchanged at 3.8% in September rather than rising to 4.0% as both the consensus and the BoE anticipated. The expected upward pressure from fuel base effects was offset by markedly lower food inflation with the rate falling from 5.1% in August to 4.5% in September.

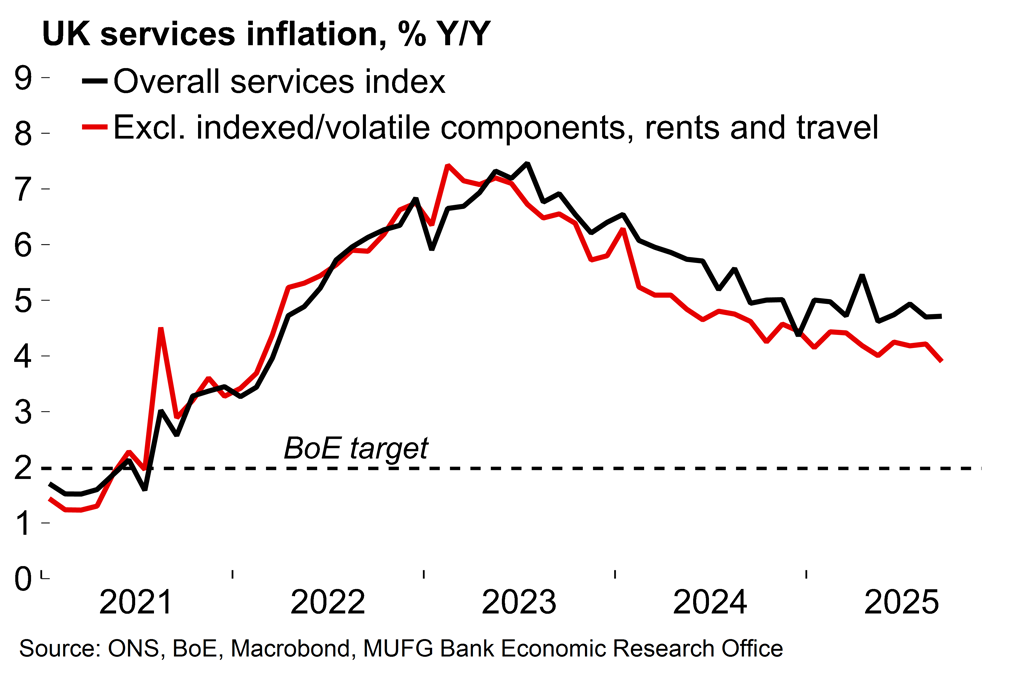

This development certainly weakens the argument made by more hawkish MPC members that higher food prices, which are salient for household inflation expectations, could result in a structural shift in price and wage setting. Food inflation is now 0.5pp below the BoE’s August projection. There was also an undershoot in services inflation, which came in unchanged at 4.7% (BoE: 5.0%). The BoE’s measure of services inflation which excludes indexed and volatile components eased to 3.9%, the lowest rate since 2022.

Looking ahead, we believe that UK inflation has now peaked. Last week’s data showed further signs of labour market slack and private sector pay pressures continue to cool. Against that background there’s scope for headline inflation to gradually ease over coming months and before moving a leg lower next year on base effects.

In terms of the implications for the BoE, our call for a December rate cut (see here) clearly looks stronger now. A November move – and a continuation of the quarterly pace of cuts – seems less implausible too. While it’s likely to be a closer vote than we had assumed, a November move still feels too soon, to our minds. One soft CPI print in isolation, even with the progress on food prices, is probably not enough to offset the hawkish concerns on the MPC. It makes sense to wait for more data. There will be two more CPI and labour market releases between the November and December meetings. We also suspect that policymakers will want to have some visibility on the Budget measures after this year’s increase in employer NICs contributed to the current hump in inflation (more on this below).

That said, the next BoE meeting would certainly become more live if there is a dire PMI and/or retail sales print on Friday, for example. That is conceivable if speculation around the upcoming Budget weighs on sentiment and spending. We will release our BoE preview next week. At the time of writing, market participants are pricing in just shy of 20bp of cuts by year-end. Two rate cuts are almost fully priced by April 2026. The UK 10Y yield is down around 30bp since the start of the month.

There was upward pressure from fuel base effects but otherwise it was a story of broad-based disinflation

The BoE’s gauge of underlying services inflation has fallen below 4%

The UK government also seems to have learnt some lessons on inflation

Turning to fiscal policy, there are now five weeks to go until the Autumn Budget. In terms of the overlap with the monetary policy outlook, it’s unclear if the UK chancellor will immediately benefit from the recent market moves set out above. While the OBR has some flexibility around when it takes its snapshot of market variables for its projections, it normally does so well ahead of the fiscal event. Prior to this year’s Spring Statement on 26 March, the OBR considered a 10-working day window up to 12 February. The Budget will be held on 26 November.

The Treasury has already received the first and second round pre-measures projections from the OBR. The chancellor has since confirmed that the OBR has downgraded its productivity assumptions, in line with earlier reports. But we can probably infer from the lack of any obvious trial balloons in the media about more radical policies that there were no nasty shocks and that the expected 25-30bn of fiscal consolidation is broadly valid.

The government has also been making noises around a possible focus on lower inflation, so it seems that a lesson has been learnt from last year’s employer NICs increase. There have been some reports that VAT on household energy may be reduced from 5% to zero. Zero-rated household energy could shave around 15bp off headline inflation, all else equal (would it provide cover to finally increase fuel duty?). We’re also watching for the UK Low Pay Commission’s recommendation for the 2026 minimum wage increase, which is due by the end of October. The government usually adopts the recommended increase, but retains discretion to modify it.

We will set out a full UK Budget preview next month, but it has also been notable to hear the chancellor suggest that she is “looking” at spending cuts too. The assumption had been that the core of the Budget would be tax rises (e.g. frozen income tax thresholds and other small measures like a gambling levy). The details will be key for market participants as there’s usually room for some gaming of the OBR projections around the timing/profile of spending commitments.

We’re not convinced that the chancellor will grasp the nettle and make any meaningful efforts to reduce welfare spending commitments after the two previous U-turns and political fallout in that area. Still, a relatively market-friendly Budget outcome (i.e. with inflationary measures avoided, some spending cuts introduced and potentially even an increase in headroom to the fiscal rules) doesn’t seem far-fetched now. It will be the government’s third attempt at reclaiming the fiscal narrative and there are some suggestions that lessons have been learnt from previous errors. There’s clearly still scope for sentiment to weaken over coming weeks as sentiment around the Budget increase. But with an uptick in inflation avoided, BoE cuts seeming more likely and no nasty surprises in other recent data (e.g. public finances and monthly GDP) the mood music around the UK economy has improved somewhat this month.