- It’s a year since the UK election but it’s not looking like a happy anniversary for the government. After a U-turn on welfare reform, speculation around the future of the UK’s chancellor has prompted a sharp sell-off in UK debt amid fears of a shift towards looser fiscal discipline.

- There are no easy options here. The government had already been sailing close to the wind with its fiscal policy. Any change to the fiscal rules now would undermine credibility and likely result in counterproductively high borrowing costs. On the flip side of that, a broader policy reset with policymakers revisiting their red lines on tax increases in order to meet current fiscal rules looks politically unviable.

- More broadly, policy volatility and speculation has undermined hopes that this government, with its large majority, could usher in a growth-friendly period of stability. UK growth is likely to have slowed sharply in Q2 which could increase the sense of gloom around the outlook with a risk that weaker sentiment will weigh on activity in H2.

Speculation around the future of the UK’s finance minister has triggered a sharp increase in borrowing costs

Happy anniversary. It’s almost a year to the day since the UK’s government was elected with a large majority and the PM finds himself facing his most significant political challenge to date. Right now, it seems unlikely that there will be many celebrations in Downing Street amid speculation that the chancellor, Rachel Reeves, is set to be replaced after the government was forced to backtrack on its high-profile welfare reform.

Looking back, there was very little to write home about in terms of Labour’s policy proposals, but we admit that we were somewhat optimistic that a return to stability after the turbulence of the Brexit years, which saw five prime ministers in six years, would ultimately create better growth conditions. That story has quickly unravelled with policy U-turns and now the speculation around the ousting of the chancellor, which triggered a sharp increase in gilt yields.

Ultimately this is a government which faces a precarious fiscal situation and cannot escape from that reality. To recap, the government’s main error was to box itself in with self-imposed red lines preventing changes to the UK’s main sources of tax revenue (income tax, VAT, corporation tax and employee NI – see here). That was despite the tough fiscal inheritance and the decision prevented a reversal of the previous government’s pre-election giveaways in the form of NI cuts. Since that point it has essentially been playing catch-up.

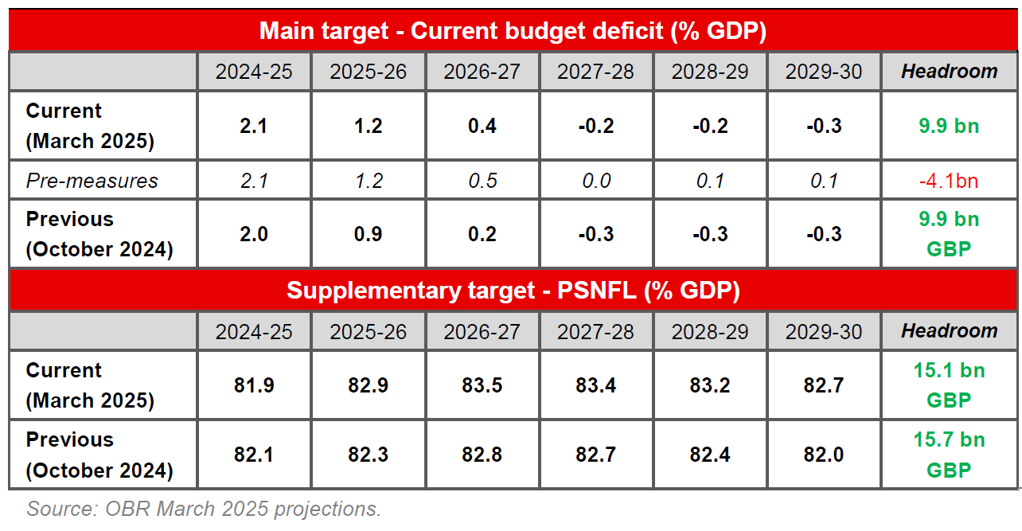

The messaging around the first budget was another unforced error with PM Starmer saying well in advance that it would be “painful”. Fairly unsurprisingly that saw speculation around possible measures weigh on sentiment. The Budget itself wasn’t actually that bad with the ‘pain’ coming mostly in the form of slightly higher employer national insurance contributions (see our take here). Market participants seemed relatively sanguine about the change to the fiscal rules which allowed a degree of higher borrowing to fund investment. But the government left itself a narrow path to tread with headroom of just 0.3% of GDP against its new primary target for the current budget to be in surplus.

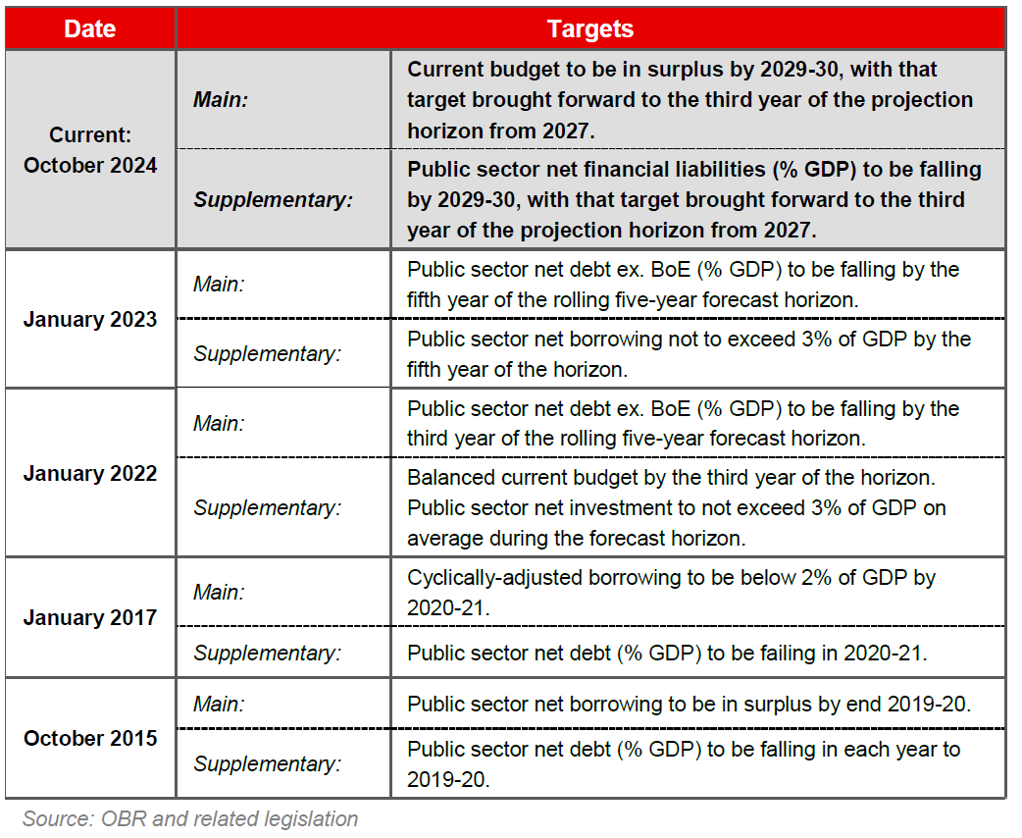

OBR fiscal rule projections

Policy uncertainty may increasingly become a headwind for growth

By the time of the Spring Statement this March, higher interest costs and weaker receipts had entirely eroded the government’s leeway against those loosened fiscal rules. The government then restored its headroom to where it was previously by announcing it would tighten the eligibility requirements for health-related benefits (see here). Those welfare reforms have now been shelved after it became apparent that there may not be a majority for the change in the governing Labour party.

It is not that decision in itself that has prompted today’s sell-off in UK gilts. Instead, market moves reflect speculation that a new chancellor would be less committed to meeting the fiscal rules than Reeves (who always made efforts to stress that this was a priority) and could even change the rules again to carve out more space for spending. Moving the goalposts once more would clearly be damaging for credibility and likely result in counterproductively higher borrowing costs.

Assuming the government does stick with the current framework, it would likely still need to find somewhere in the region of 15-25bn of savings even if today’s increase in borrowing costs were to reverse. Getting anywhere near this mark looks difficult under a government that is either unprepared or unable to take politically difficult decisions. A broader policy reset – perhaps with a new chancellor who is prepared to revisit the government’s pre-election red lines on tax rises – does not seem especially likely at the moment, but could become more plausible given today’s market reaction. As things stand, Reeves remains chancellor and is due to speak at Mansion House on 15 July, an event which now looks set to take on added significance.

More broadly, any hope that some stability under a government with a large majority and still four years to the next election would support activity now looks decidedly optimistic. The government has stated that it is focused on growth but, some planning reform aside, seems to shy away from any sort of politically difficult decisions which could boost activity further ahead. On top of that, most of the planned increase in capex has been swallowed up by energy and defence spending which don’t necessarily have obvious productivity-boosting potential. In terms of the more immediate outlook, we expect growth will slow meaningfully in Q2 (see here). That could add to the sense of gloom around the UK economy over coming months if the government can’t reclaim the narrative.

UK fiscal rules since 2015