- Vietnam is embarking on its most ambitious set of structural reforms since its landmark Doi Moi reforms in the 1980s.

- We think the most fundamental change is the shift to making the private sector the most important driving force in Vietnam’s economy, in a way that has not been done throughout Vietnam’s recent history, not least since Doi Moi.

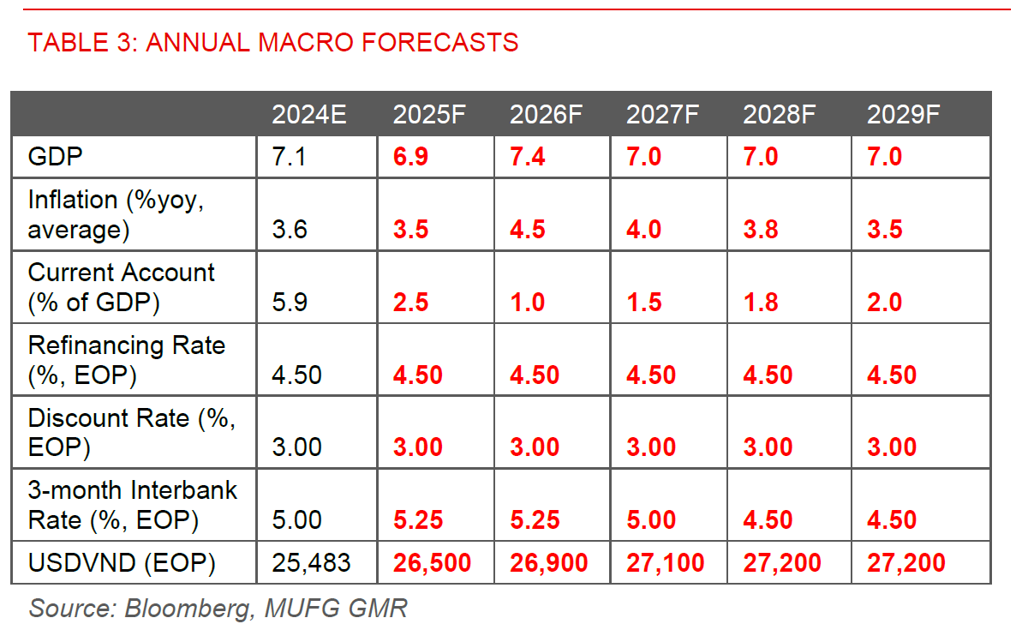

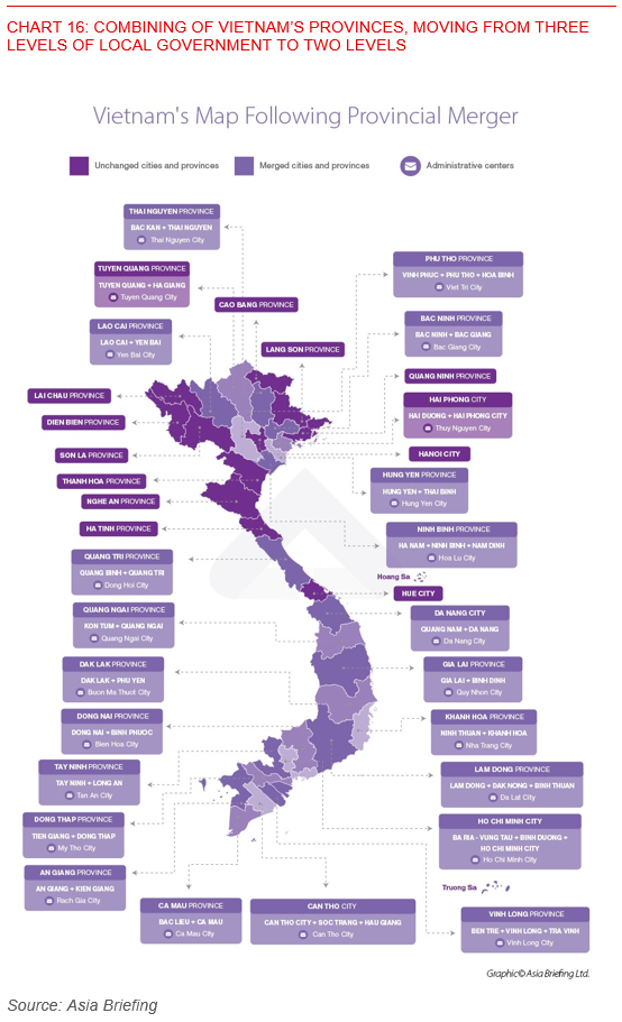

- Crucially, these are not just theoretical aspirations. There have been a whole multitude of policy changes implemented in 2025, and we suspect more are to come in the months ahead. Key examples of reforms include a meaningful downsizing of the public sector, combining and streamlining provinces, a targeted 30% reduction in bureaucratic red tape, reinvesting savings into factors such as science, public education and infrastructure, developing 20 large national companies plugged into global value chains, among many more.

- The longer-term aspirational goal by the government is to hit high income status by 2045, and in the near-term also pushing hard for a GDP growth target of more than 8% this year.

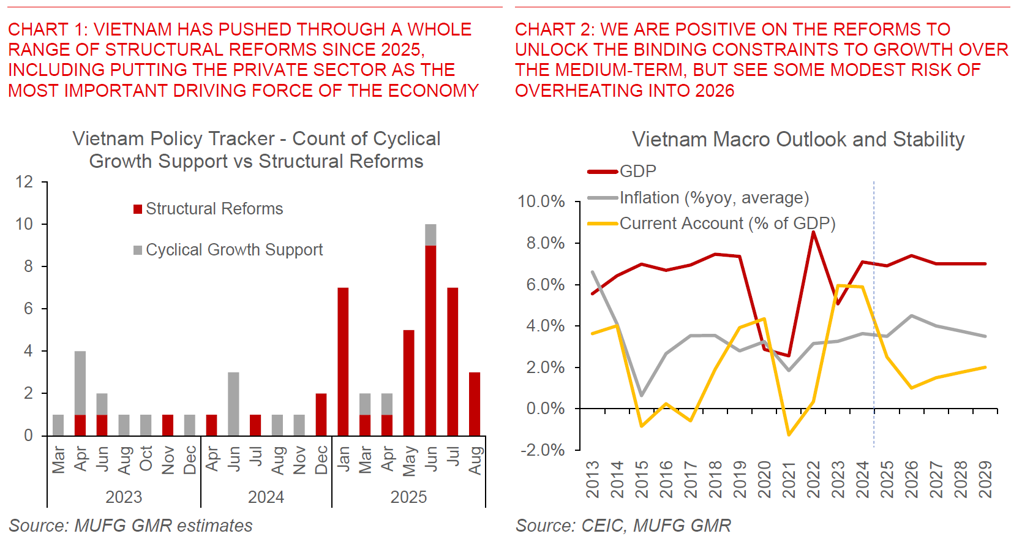

- We are very positive on the ability of these reforms to unlock the binding constraints to investment in Vietnam over the medium-term. Nonetheless, over the near-term we see some risks that Vietnam’s economy grows somewhat above trend, at least until productivity improvements dominate.

- All-in, we raise our Vietnam GDP forecasts to 6.9% in 2025 and 7.4% in 2026, with stronger domestic demand and better private sector confidence helping to offset export drag in 2H2025. We see inflation rising closer to 4.5% in 2026 before moderating thereafter reflecting the lagged impact of stronger domestic demand and credit growth. Meanwhile we forecast the current account surplus to narrow to around 1% of GDP in 2026 from an estimated 2.5% in 2025.

- Over the medium-term, we expect Vietnam’s growth to trend above 7% - not the above 8% rate the government aspires to – but certainly far better than the 6% seen over the past decade with domestic reforms the key driver.

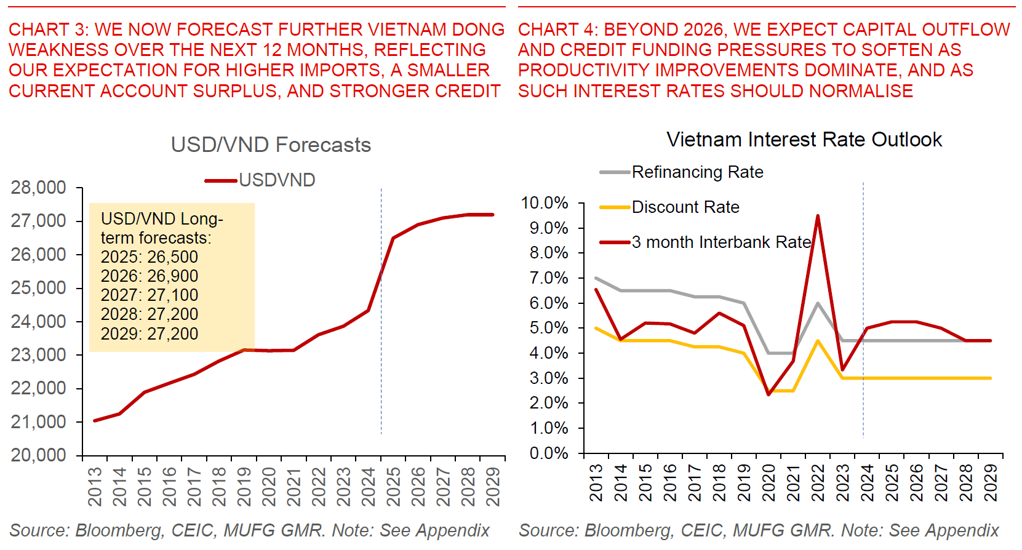

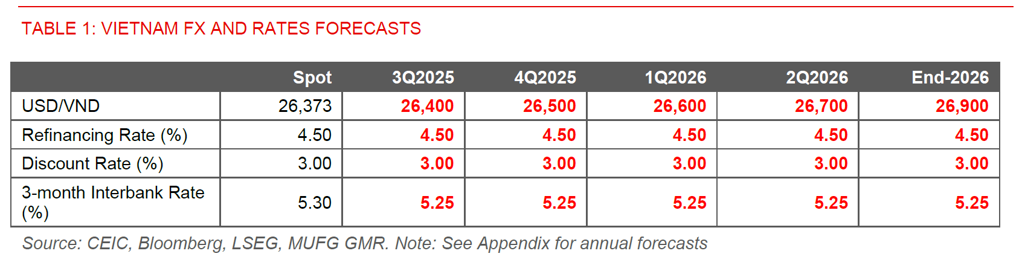

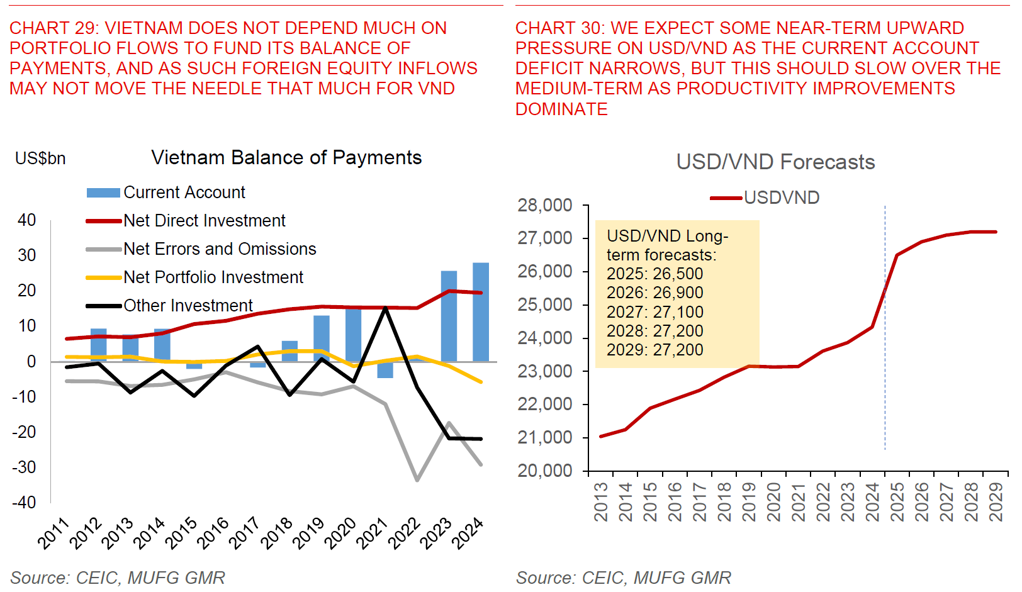

- We now raise our USD/VND forecast to 26,500 by end-2025 and 26,900 by end-2026 (from 26,300 and 26,000 previously) reflecting higher import needs, a narrower current account surplus, and more robust credit growth.

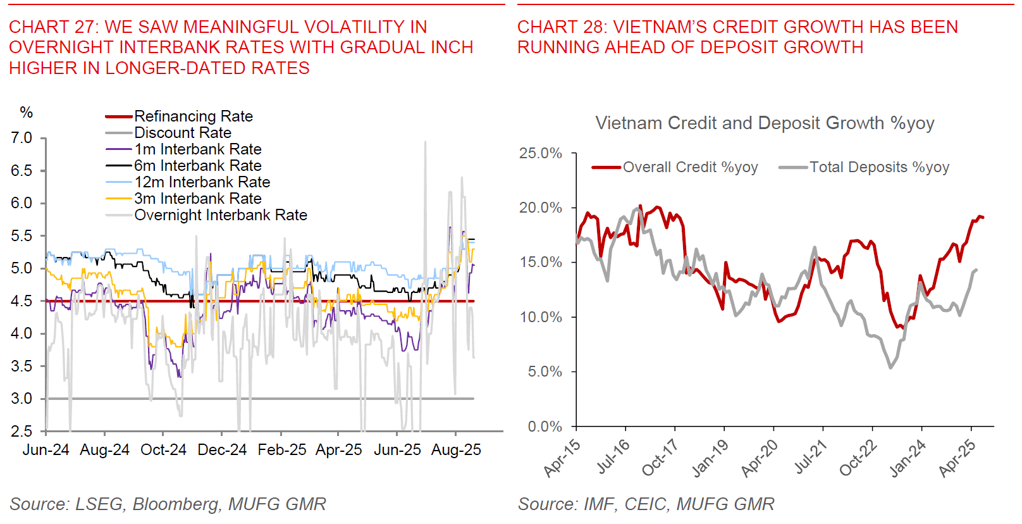

- We also now expect SBV to keep policy rates on hold at 4.50%, from our previous forecasts for 50bps of rate cuts. This is even as we continue to expect the Fed to cut rates to around 3.00% by 2026. There could also be upward pressure on interbank rates, reflecting looser credit conditions.

- Over the medium-term beyond 2026, we could see the pace of VND weakness tapering off. Reforms should over time help to improve private sector confidence and raise productivity. We also note that relative to our forecasts for the USD to weaken, our forecasts imply further trade weighted exchange rate weakness for VND.

Vietnam’s Resolution: Transform to Reform, Optimise to Mobilise

Vietnam is embarking on its most ambitious set of structural reforms since the country’s landmark Doi Moi economic reforms in 1986. While this is in part catalysed by the external uncertainty brought about by tariffs from the Trump administration, the broader context for Vietnam is that the demographics dividend is turning far less favourable at the same time as its economy remains focused on lower value-added economic activity including in the manufacturing sector for now. Meanwhile, Vietnam has since 2021 gone through a very painful credit and real estate downcycle, with the negative effects still lingering, sparked in part by a freeze up in the corporate bond market and exacerbated by the Saigon Commercial Bank bank run and the Covid-19 pandemic. Vietnam as such risks being stuck in the middle-income trap even as external trade and geopolitical conditions are likely to become far less favourable over the medium-term.

It is in this broader context that Vietnam’s top leadership has pushed through a whole range of structural reforms since late 2024.

Key changes include Resolution 68 to make the private sector “the most important driving force” of Vietnam’s economy, a significant restructuring and downsizing of the public sector, combining and streamlining of provinces, among many others (explained in greater detail in subsequent sections).

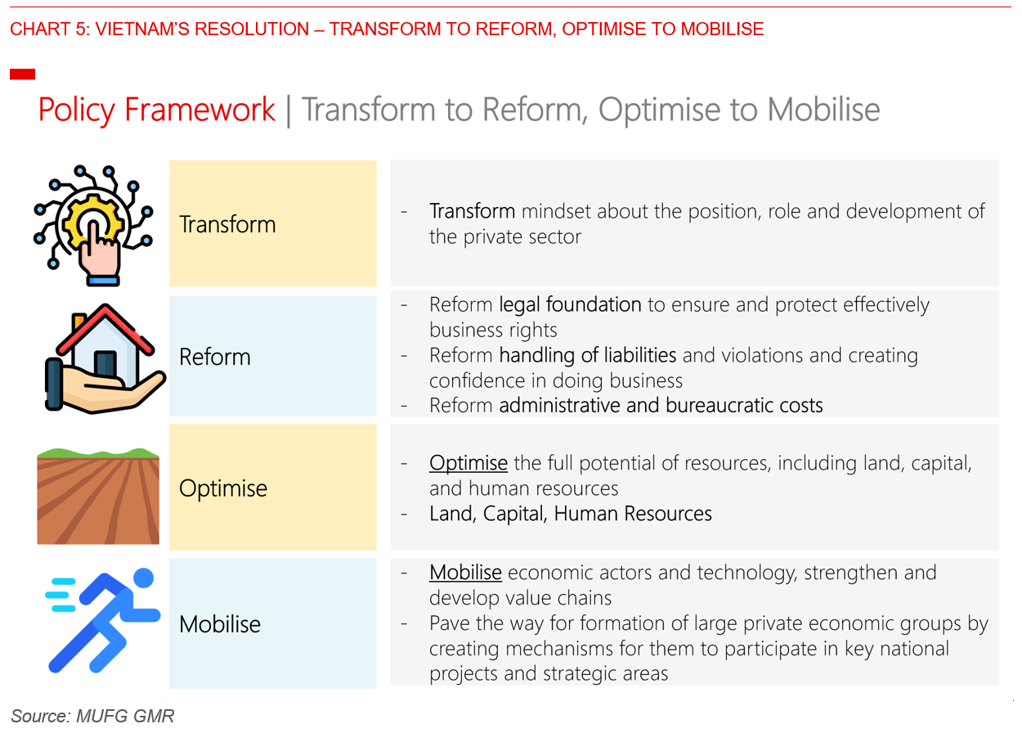

We think the key strategy can be summarised in one phrase at a high level – “transform to reform, optimise to mobilise”:

“Transform to Reform, Optimise to Mobilise”

Transform to Reform: This step involves transforming the mindset of the entire society across a variety of levels including public and private, with fundamental reforms encompassing legal, bureaucratic, human resource, and institutional. Concrete examples include:

- Reforming Vietnam’s legal foundations to effectively protect business rights

- Significantly cutting administrative and bureaucratic costs by at least 30% by 2025, and even more so beyond that

- Moving from pre-approval licensing to post-approval supervision system

- Reforming the handling of violations and liabilities, while giving priority to civil proceedings where reasonable and practical

Optimise to Mobilise: This involves optimising the usage of existing resources, while mobilising a whole gamut of economic actors and new resources such as science and technology, human capital and infrastructure. Examples include:

- Optimising the public sector and provincial governments through downsizing and combining, to make them more efficient and productive for the future

- Reinvest the freed-up resources into areas such as public infrastructure, education and science and technology

- Mobilise factors of endowment including land, capital, skilled workers, technology, and innovation

- Catalyse economic actors especially the domestic private sector – both large and small companies alike

- Strengthen and develop global value chains and with that also subject domestic companies to global competition

Not just theory, meaningful policy changes are happening in 2025 as we speak

The important point is that these are not just theoretical aspirations.

We have already seen real and meaningful implementation of many of these policies in 2025. If the current trajectory continues – which we think is likely - we expect the outlook and landscape of Vietnam’s economy, sectors and markets to be transformed for many years to come.

In addition, as we will argue in this report, we think that policymakers are also aware of lessons learned through history, both in Vietnam’s case during the expansion of State-Owned-Enterprises in the late 2000s, and also the eventual downsides from other countries’ experience such as South Korea’s Chaebol strategy.

Good outcomes are of course not pre-destined, and there are important risks we have to watch out for. These include the risks of excessive credit growth, macro and financial instability, inflation, currency depreciation, and the inefficient rollout of public infrastructure, among many others.

Nonetheless, the crucial question is whether the policy direction taken is the right one – and we think the answer to that is yes. As such, even if there might eventually be some stumbles and policy missteps along this road, as long as these problems and issues do not ultimately prove fatal, one can still pick himself or herself up and continue running, though it may prove to be a partial detour towards what is ultimately the right destination.

In subsequent sections of this report, we will first explain the meaningful structural policy changes that are taking place in Vietnam, highlight why these shifts will over time unlock binding constraints to growth and private investment. We then link this to the potential macro and market risks that corporates, investors and policymakers should watch out for along the way. Lastly, we will conclude with the short to longer-term macro and market impact, including to FX and rates markets and the economy.

What is holding Vietnam back? 3 key problems

We see 3 key problems with Vietnam’s current growth model, even as there has no doubt been meaningful progress made especially in the manufacturing and export sector (see our previous report Vietnam: Reasons to remain optimistic while factoring in Trump 2.0 tariff risks)

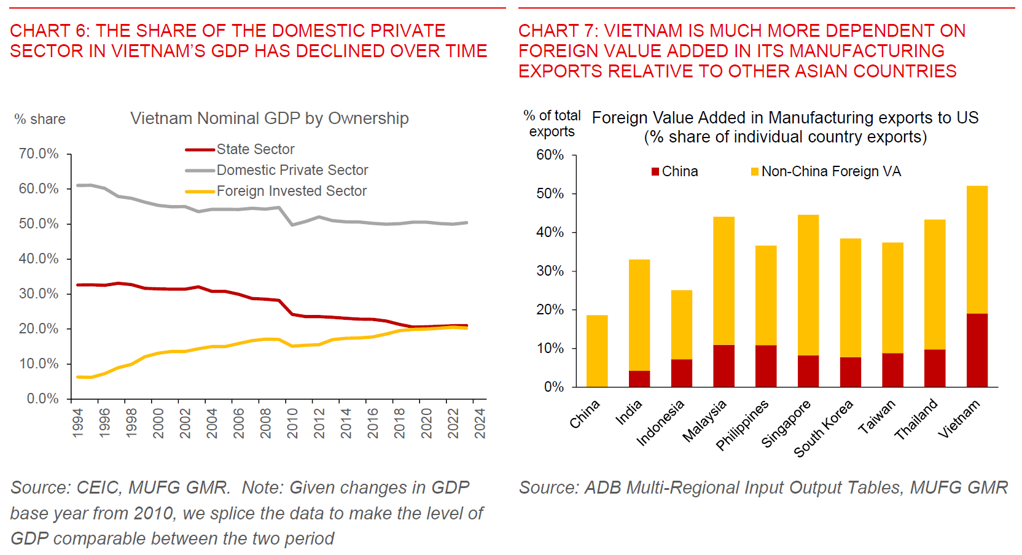

First, Vietnam’s domestic private sector has been reducing in importance as a contributor to GDP. The domestic private sector’s share of GDP has steadily dropped from around 60% in 1994 down to around 51% in 2011, and essentially staying flat at around to 50% as of 2023. In its place, the foreign invested sector (ie. FDI) has been rising as a share of GDP and as such importance (see Chart 6 below).

Second, the linkages between Vietnam’s domestic private sector and foreign invested sector are relatively low. Data from Global Input-Output tables shows that foreign value added in Vietnam’s exports is around 50%. This is the highest across Asia and points to still meaningful reliance on foreign inputs for Vietnam’s manufacturing exports (see Chart 7 below). It’s of course important to point out that domestic value added in Vietnam’s exports has been rising in absolute terms as Vietnam’s exports have risen, but the broader point we are making about relatively low spillovers to the domestic private sector are still relevant.

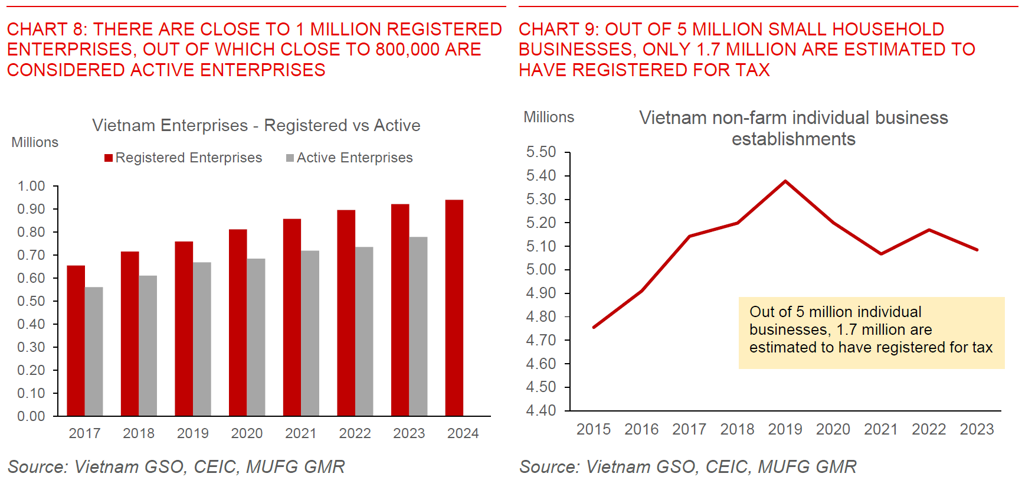

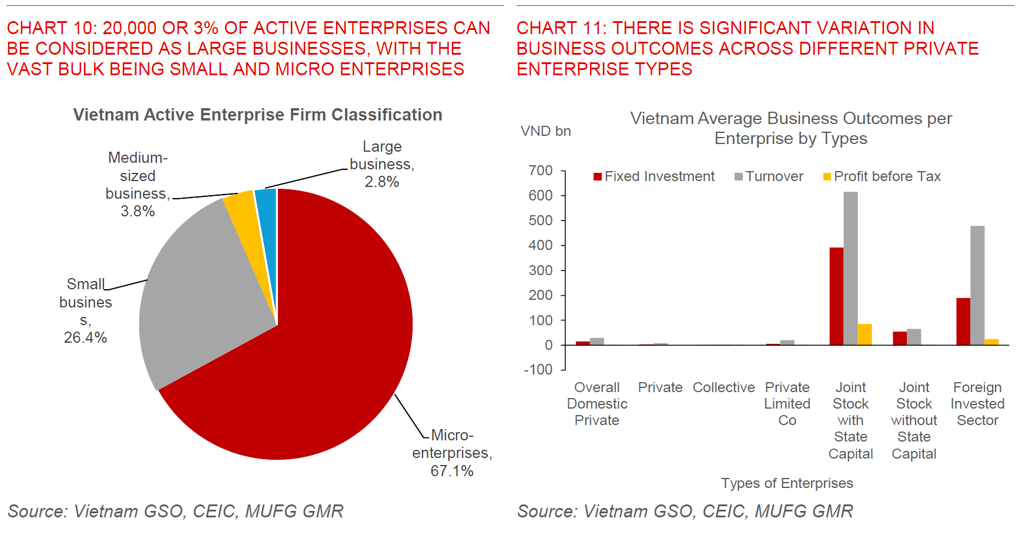

Third, there is a wide dispersion of productivity outcomes not just for Vietnam’s domestic private sector, but also within the domestic private sector. For one, Vietnam’s domestic private sector makes up more than 80% of total employment, but contributes just 50% of GDP, highlighting a stark productivity gap. Meanwhile, of the 1 million registered enterprises and 800,000 active firms, only around 20,000 can be considered large businesses (3% of total), with the vast bulk comprising of micro businesses (Chart 8 and 10). In addition, there are also an estimated 5 million small household businesses, of which only 1.7 million are registered for taxation, and is as such also a reflection of the meaningful informality in the labour market. Business outcomes vary significantly across different private sector entities, with the likes of private, collectives and private limited companies making very small revenues and profits per firm on average, especially when compared with the likes of the FDI sector (see Chart 11 below).

Resolution No. 68 – The private sector as the most important driving force in Vietnam’s economy

With these structural problems faced by Vietnam’s domestic private sector in context, we as such see the announcement of Resolution No. 68 in May 2025 by Vietnam’s top leadership, and the subsequent implementation of accompanying policies as a positive game changer for Vietnam’s economy.

We think the most important breakthrough is the transformation in mindset, first from the political leadership and eventually helping to permeate to all levels of society over time.

The key change here is really bringing the private sector to the forefront as a driving force, in a fundamental shift which has not been done historically in Vietnam’s political economy, perhaps outside of periods of existential urgent reforms such as during the 1986 Doi Moi revolution.

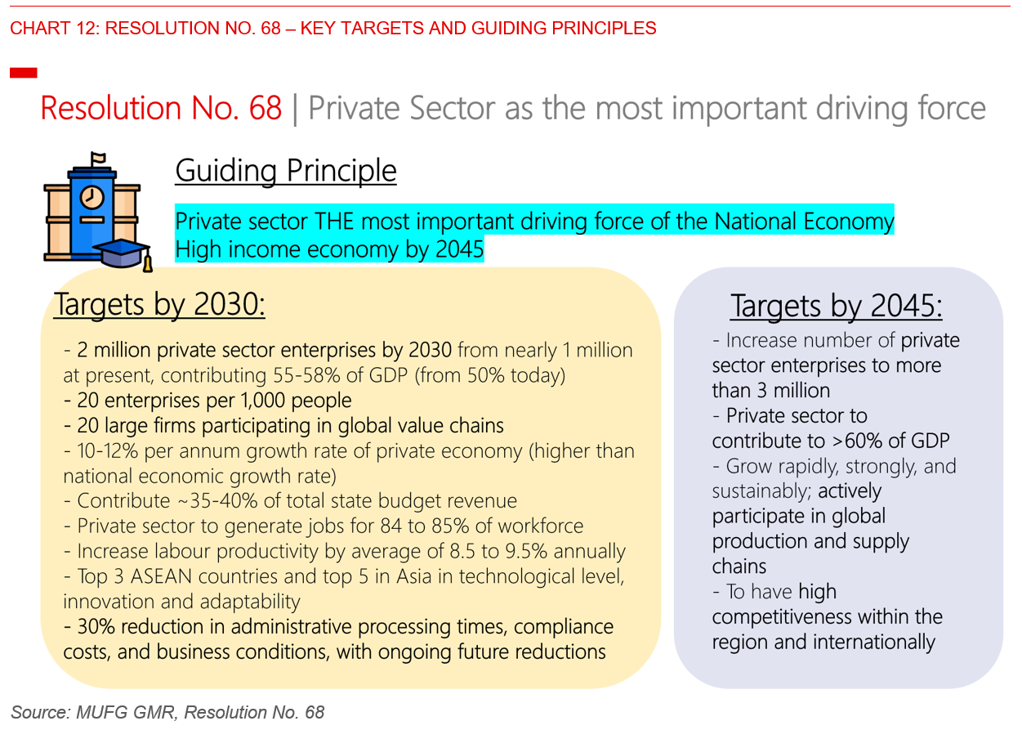

Resolution No. 68 also provides some crucial economic targets to be met, including raising the number and economic contribution of private sector enterprises, developing 20 large firms which participate in global value chains (somewhat reminiscent of South Korea’s Chaebol model), aspiring to be among the top Asian economies in technological innovation, eliminating unnecessary business regulations, among many others (see Chart 12 for the key targets of Resolution 68).

How to get there? Transform to Reform, OPTIMISE to Mobilise – The four pillars

Beyond high level targets, what is just as important are also concrete policies and frameworks that can be executed over time.

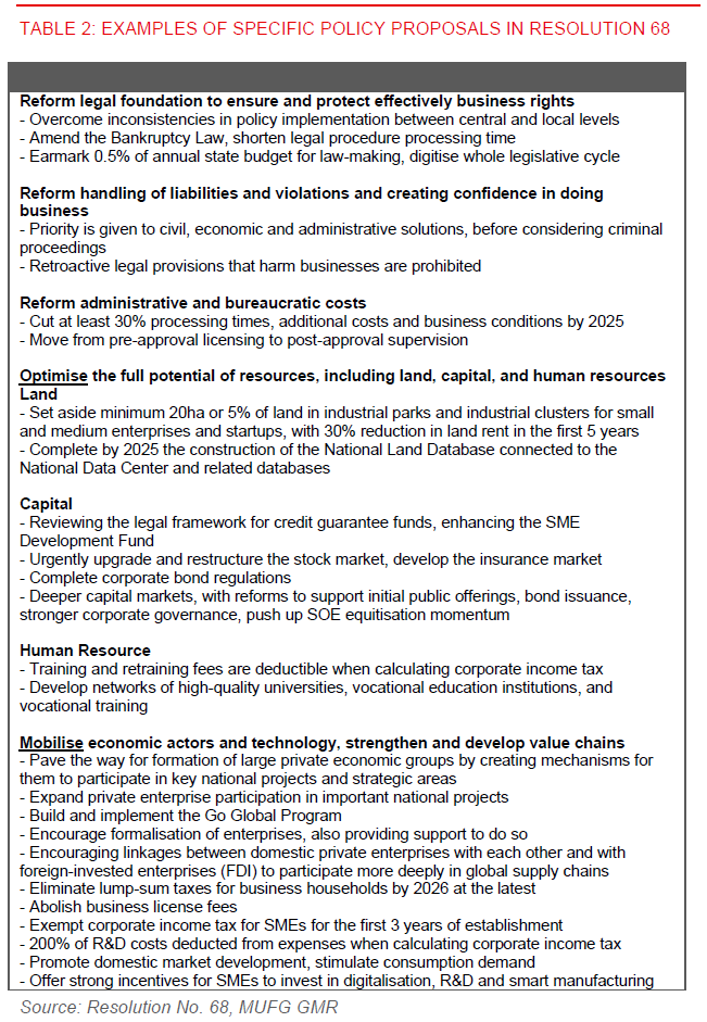

We have summarised some examples of the specific policy proposals and frameworks that are incorporated in Resolution No. 68 in Table 2 below. Just to highlight a few for instance, there are a range of tax and business incentives planned to help support small and medium enterprises. For instance, annual business license tax will be abolished from January 2026, while preferential tax rates will be applied to companies with lower revenue thresholds. There are also proposals to encourage formalisation of enterprises by exempting corporate income tax for SMEs for the first 3 years of establishment. Meanwhile, land will also be set aside for SMEs and startups, with also a 30% reduction in land rent in the first 5 years.

Meaningful implementation of key policies – we are already seeing early fruits of that labour

For us, the important point is that these frameworks and resolutions are not just theoretical aspirations. We have already seen very tangible and meaningful implementation of these policies in 2025, and many of which are significant structural shifts in their own right. If the current trajectory continues – which we think is likely - we expect the outlook and landscape of Vietnam’s economy, sectors and markets to be transformed for years to come.

We highlight four main areas of implementation which are of note. These key areas include:

- Bureaucratic Reforms

- Institutional Reforms and Public Infrastructure Programs

- Human Resource Reforms

- Science and Technology Reforms

Bureaucratic reform – significant transformation at both the public sector and provincial levels

There have been very significant policy shifts happening at both the public sector and also provincial level, and with the overall objective to streamline existing resources and also improving bureaucracy and efficiency.

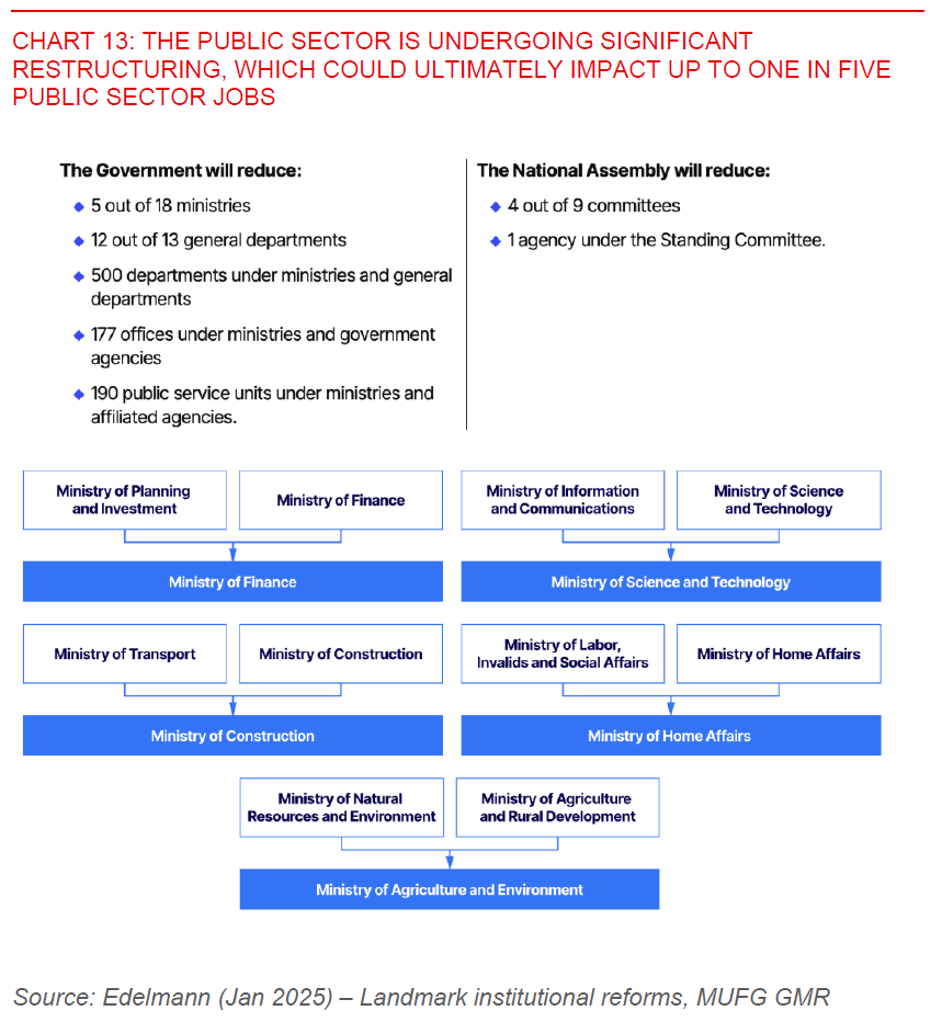

First, the government has dissolved and merged agencies at both the central and local levels. First announced in early December 2024, all ministries and ministerial-level agencies will undergo internal organisation reforms. The number of Ministries will be reduced to 13 from 18 previously, with for instance the Ministry of Planning and Investment and the Ministry of Finance combining, the Ministry of Information and Communications and the Ministry of Science and Technology merging, while the Ministry of Transport and Ministry of Construction also combining, among others (see Chart 13 above for a summary). There will also be restructuring of the National Assembly with a meaningful reduction in number of committees.

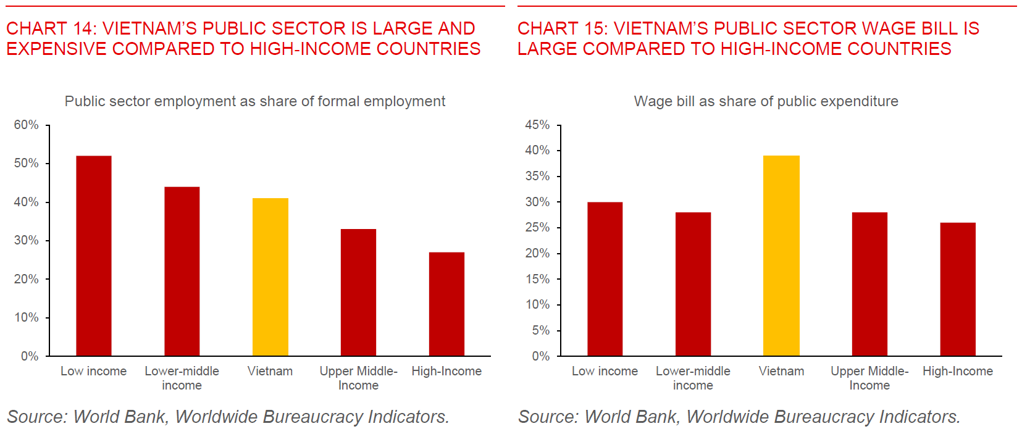

The broader policy objective is to reduce the burden on the state budget with the aim of lowering the wage bill and also recurrent expenditure, redirect more resources towards other key areas of economic development such as infrastructure and innovation. Importantly the key is to also create a more efficient public sector, while also fostering a more conducive environment for businesses.

Of course these moves also come with costs, especially in the near-term. The changes could ultimately affect one in five public sector jobs, but with compensation set aside for those who have been affected by the restructuring. Meanwhile, the restructuring of the various Ministries may also mean some near-term uncertainty on licensing approvals and navigation of the bureaucracy by companies and investors.

We note that these changes cannot be taken in isolation of broader human resource reform including in the public sector, such as raising public servant salaries over time, together with a meaningful revision in how the country recruits, manages and evaluates its workforce, and efforts to attract the best and brightest globally to work for the public sector (see section on human resource reforms).

The second key bureaucracy reform is the combination of provinces, with the number of provinces and municipalities reduced from 63 to 34. In addition, there is a shift to a two-tier local government system (province and commune), from a three-tier system previously (province, district and commune). As a result, the number of administrative units will decrease by approximately 60 to 70%. The broader context is that the size of inhabitants per region/state for Vietnam seems larger compared with other countries, and the hope is that this will also ultimately drive improvements in administration and efficiency at the provincial level. Our understanding is that these moves are not about centralisation, but rather viewed more as a flattening of the hierarchy with the removal of the district layer. As such, continued de-centralisation will still be key moving forward in helping to implement central government policies and activities at the local level.

Institutional Reform and Public Infrastructure – creating national champions

Next is institutional reform and public infrastructure spending. This is very closely linked to the moves to reform the bureaucracy, given the broader policy objective under Resolution 68 to reduce administrative costs and regulations by 30% by 2025, and to also redirect resources to areas with of national strategic importance.

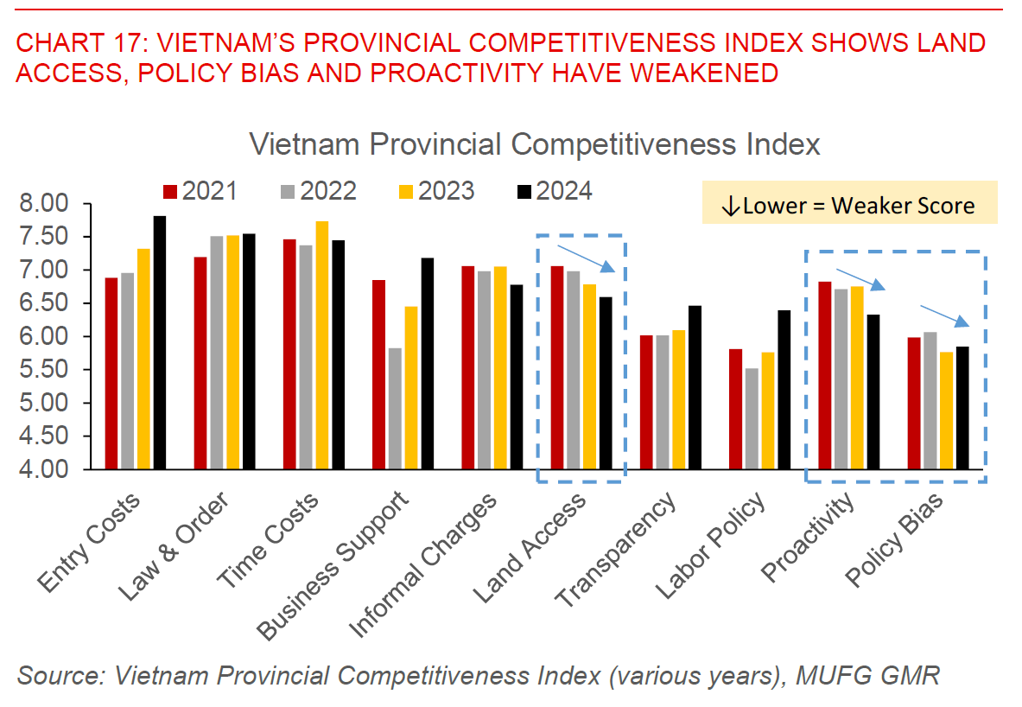

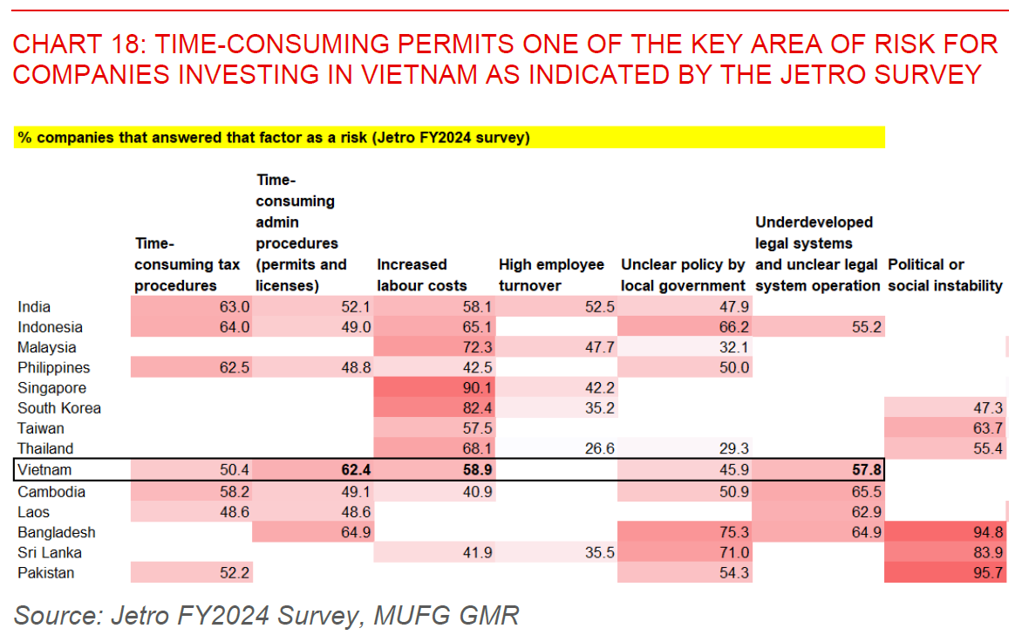

For one area in institutional reform, the move from a pre-check approvals to now a post-check supervision system including for the business and land licensing process has based on our understanding and conversations already led to a positive impact on the ground among key businesses. A variety of business surveys indicate that permits, licensing and regulation is a key area of concern among businesses when doing business in Vietnam. For example, data from the Vietnam Provincial Competitiveness Index shows that areas of land access, proactivity and policy bias by provincial governments have been weakening over the past few years, even as other areas such as business entry costs and business support have been improving over time (see Chart 17 below). 67% of firms surveyed in the 2024 PCI said that land dossiers were processed longer than the listed or regulated period, while a significant 74% of firms surveyed have to delay/cancel business plans due to difficulties in completing land applications. In addition, latest FY2024 surveys by the Japan External Trade Organisation (JETRO) shows that 62% of firms surveyed said time-consuming administration procedures is a key risk factor when it comes to expanding in Vietnam (see Chart 18). As such, if the moves by Vietnam government to reduce administrative and licensing costs are meaningful, these can go a long way to unlocking further private investment.

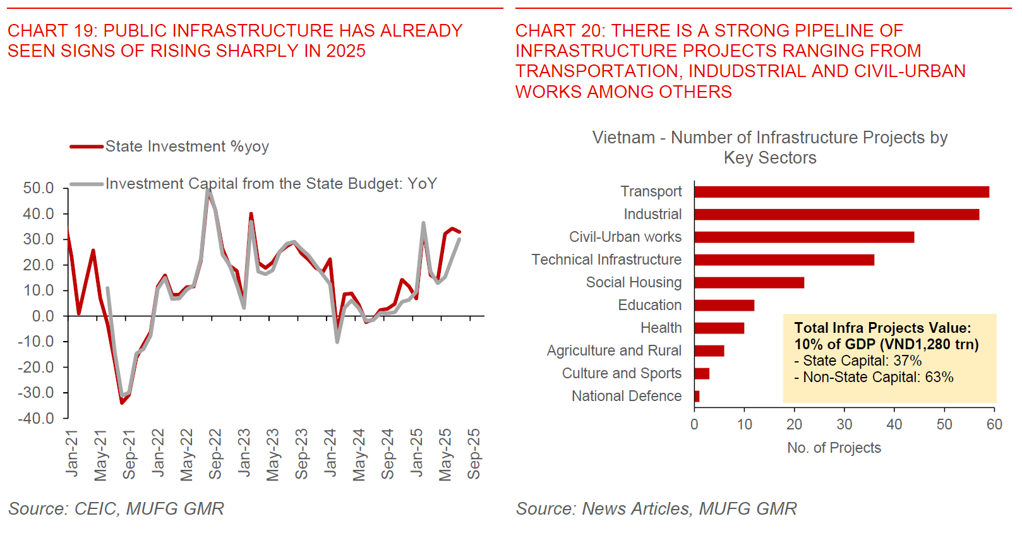

The second key area in institutional reform where there has already been a substantial policy push is in public infrastructure rollout. By extension is also the push to create 20 large local companies including through plugging them into bidding for National strategic infrastructure projects and also subjecting them to global value chains and competition. Public infrastructure spending has already risen quite sharply as of the latest print in June by around 30%yoy. Based on our understanding, the preference and priority has been for local large companies to bid for these projects and subsequently also tap expertise of foreign companies in order to plug their existing gaps in know-how when it comes to construction depending on the projects. The hope is that this will also ultimately result in learning-by-doing over time and some technological transfer, with the greatest initial spillovers captured by local companies.

Based on the latest plans, the government has announced a very strong pipeline of infrastructure projects worth more than 10% of GDP, ranging from a variety of sectors such as transportation, industrial and civil-urban works. State capital is expected to fund around 37% of the value of these projects, while private and non-state capital is expected to fund the rest (see Chart 20 below).

We will come to the macro risks later of this approach, but the broader point we are making here is that there has been very quick implementation of this key prong of institutional reform and with that also fast rollout of public infrastructure projects.

Human Resource Reforms – across both public and private sectors

Next, there are also very meaningful policy efforts to raise the quality of human resources in the country across a variety of spectrum.

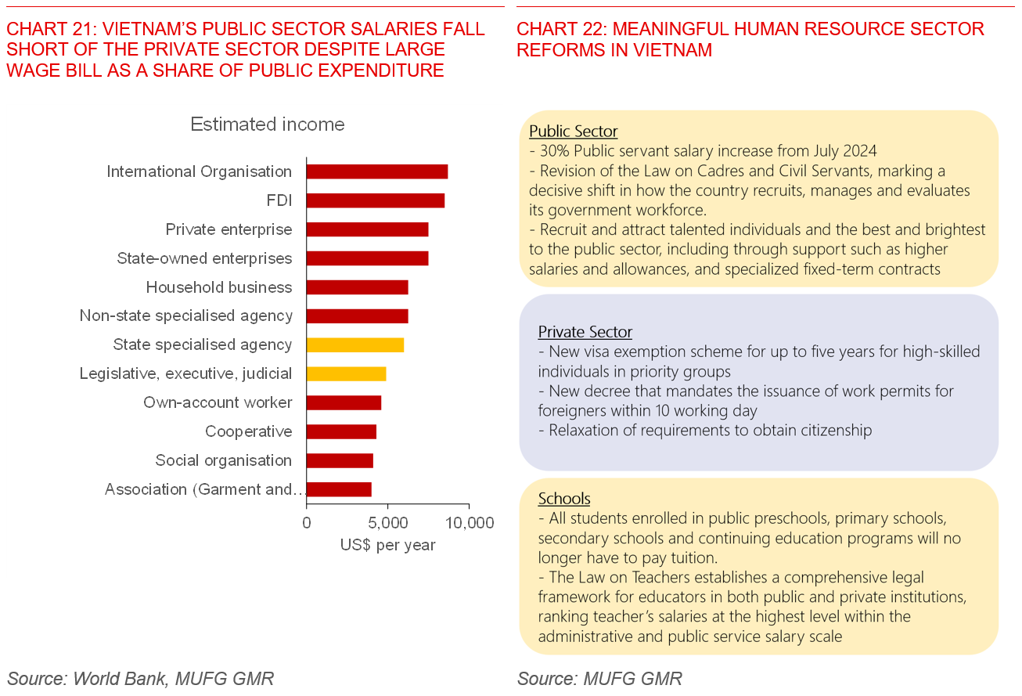

First, on the public sector, Vietnam is implementing measures to both increase remuneration and better assess public servants to retain the existing talent pool, even as the government has streamlined the public service by making it much leaner as mentioned in the earlier section. With the income gap between public servants still persistent, the priority on this front is quite urgent (see Chart 21). There has already been a 30% public servant salary increase implemented from June 2024, with likely more salary increases to come in the coming years. In addition, a recent revision of the Law of Cadres and Civil Servants helps to fundamentally change how the government workforce is evaluated, and as such should continue to improve the efficiency of human resources within the government.

Beyond that, Vietnam’s public sector is also making meaningful efforts to attract talented individuals across a range of fields and skills, in a way which has not been done in the past. These measures include providing greater support for sought after talent including higher salaries and allowances, together with specialised fixed term contracts so that these domain experts could be more incentivised to join the public service and as such provide their expertise.

On the private sector side, there are also a whole range of schemes and policies rolled out this year to attract more talent including foreign talent. These includes new visa exemptions for up to five years for high-skilled individuals in priority groups, a new decree that mandates the issuance of work permits for foreigners within 10 working days, together with relaxation of requirements to obtain citizenship.

Lastly, on schooling, Vietnam’s leadership has recently passed a significant policy to eliminate tuition fees for all public schools from pre-school to high school. Students in private institutions will also be eligible for government subsidies, with the government working towards universal pre-school education by 2030. At the same time, in a bid to make the teaching career more fundamentally attractive as a career, a new Law on Teachers has been passed to establish a legal framework for educators. Among other elements, teachers’ salaries will now be ranked within the highest level in the administrative and public service salary scale. All these moves on the education sector and human resource policies will take time to bear fruit but if sustained will be good from a fundamental long-term growth perspective.

Science and Technology Reforms

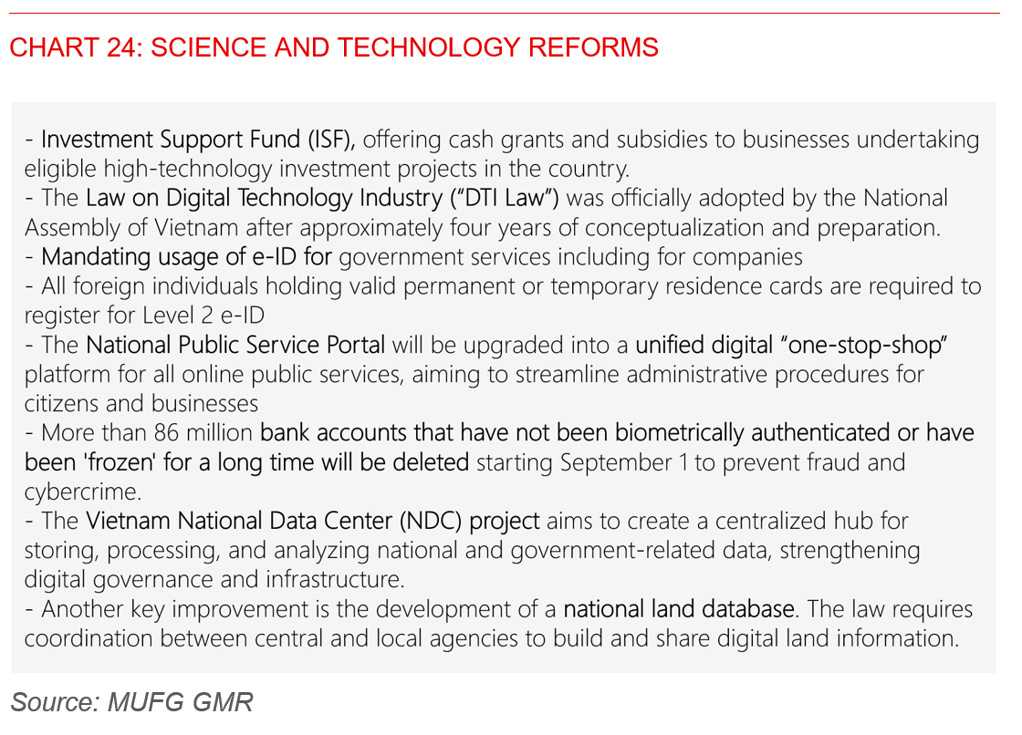

Last but not least, there have been a whole host of policies to tap more on science and technology as a key growth driver, and also in the broader context of Resolution No 57 targeting to place Vietnam in the top 30 countries in the world for innovation by 2045 with the digital economy exceeding 50% of GDP by then.

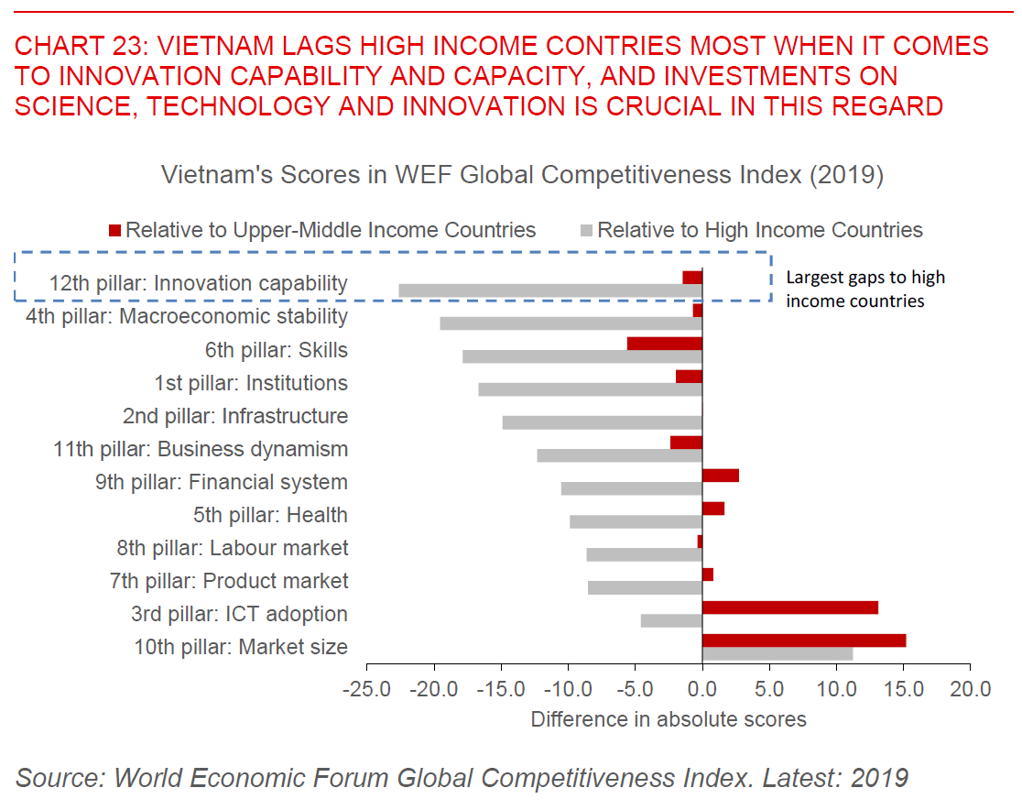

For Vietnam to reach its aspiration of a high income country by 2045, innovation and technology will be a very key plank. The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index shows that relative to high income countries, Vietnam face the largest gap in innovation capability, including in areas such as R&D expenditure and patent applications, even if fundamental ICT adoption is relatively good by contrast (see Chart 23 below).

Since 2025, key policy thrusts on science and technology for Vietnam includes the usage of Digital ID for all government services including companies, upgrading the National Public Service portal to a unified digital “one-stop-shop” platform for all online public services, creating a National Data Center for storing, processing, and analysing national and government-related data and strengthening digital governance, together with establishing an Investment Support Fund to offer cash grants and subsidies to businesses undertaking high-tech projects in the country (see Chart 24 above for a summary).

Key macro and market risks – credit growth, short-term disruptions, FX weakness

We are positive on the multitude of these significant and meaningful policies and reforms by Vietnam, starting from the push to make the private sector the most important driver of the economy through Resolution No 68, and also the whole range of policies including in bureaucracy reform, human resource reform, institutional reform, and science and technology reform.

Nonetheless, there are key risks that we have to watch for, and these will also have macro and market implications including for our FX and rates forecasts.

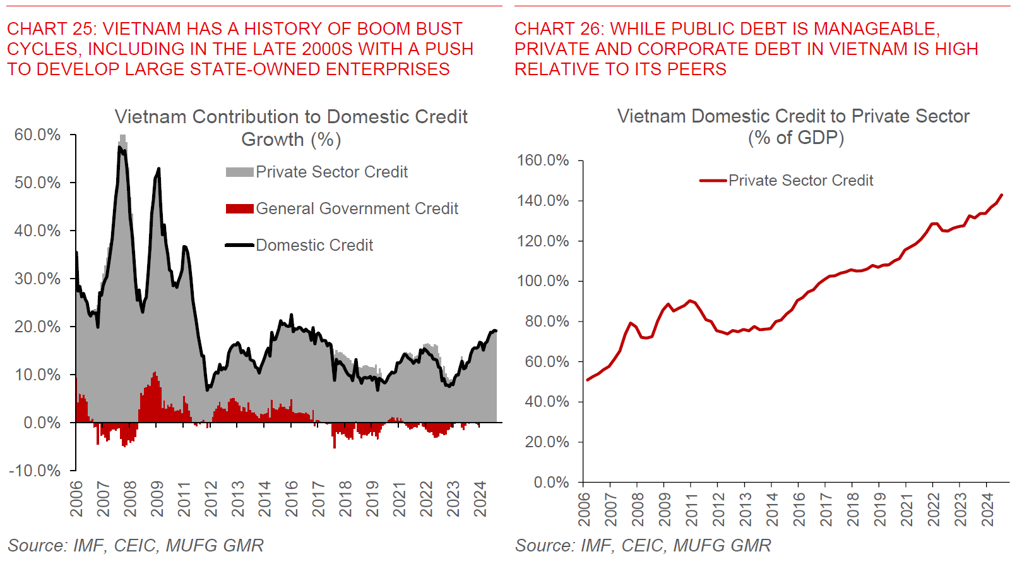

One important risk we are watching for is on excessive credit growth. Vietnam’s economy has a long history of boom bust cycles exacerbated by banking and financial system. The most recent episode was in 2021 with the fall of Saigon Commercial bank and preceeded by a freeze-up in the corporate bond market due in part to weak credit underwriting standards and exposure of retail investors to the fast-growing nascent market back then. Throughout Vietnam’s history as well, the most pertinent and impactful cycle was back in the late 2000s to early 2010s, where there was a meaningful push to develop large state-owned conglomerates.

We emphasise that we are in a different part of the credit cycle today, with the domestic economy still gradually recovering from recent negative shocks. In addition, the push this time around to support private enterprises and large conglomerates is very different from the credit cycle that we saw in the past.

Nonetheless, what is true is that the government’s ambitious efforts to both push out public infrastructure and also boost growth towards 8% in the near-term could have some knock-on impact to the ability of the banking system to supply credit and funding necessary to support this aspirational growth, at least until the productivity impact of other policies such as human capital and innovation feeds in later.

We have already seen some initial signs of these distortions, with overall credit growth rising faster than deposit growth, together with some spikes in interbank interest rates. Part of this liquidity distortions could reflect shorter-term factors such as the timing of government spending and deposits. More broadly, we think it may also reflect tighter funding conditions especially the distribution of funding for the smaller banks, with smaller banks relying more on the capital markets to fund some of their growth especially in recent months.

Over the longer-term what is an urgent priority as well for the government is to develop additional sources of funding through capital market reforms, and at the same time to ensure financial stability through controls of asset quality and risk management among banks. Vietnam is still very much bank-dominated in terms of credit supply and being able to as such diversify this funding pool to support infrastructure and growth needs of the private sector will be crucial for macroeconomic and financial stability as well. Vietnam’s Prime Minister’s recent announcement asking the State Bank of Vietnam to come up with a plan to remove credit caps brings both risks and opportunities – opportunities in a move towards a more market-based risk management, but risks of financial instability if not done right and well in an appropriately sequenced manner.

The other key risk we are watching for is on any short-term disruptions to growth through implementation of policies including public sector cuts and also moves to e-invoicing for taxation. For now, we assess the downside risks as being limited because there has also been compensation to those affected by the public sector job cuts.

The long and short of it – macro and market conclusions

To summarise, we are positive on the policy direction taken with the changes in structural reforms by Vietnam’s government, especially the focus on the private sector coupled with the multitude of policy changes such as bureaucratic reform, institutional reform, human resource reform and science and technology reforms, among many others.

In the near-term, we do however see some rise in import pressures due to the significant rollout in public infrastructure projects. Meanwhile, given the reliance on bank credit as a source of funding for the aspirational growth rates Vietnam’s leadership is looking for, we could continue to see tighter funding conditions resulting in elevated interbank rates.

From a macro perspective, we have raised our GDP forecasts to 6.9% for 2025 and 7.4% for 2026. With the rise in imports and likely slowing in exports due to the lagged impact of tariffs, we think Vietnam’s current account surplus is likely to narrow to around 1% in 2026 and as such providing somewhat less support for VND near-term. For VND specifically, while structural reform and including a possible inclusion of Vietnam into the FTSE Russell Emerging Markets Equity index may result in higher foreign portfolio inflows, we note that Vietnam does not depend that much on portfolio inflows to fund its balance of payments (see Chart 29 below). The key element that could move the needle for FX is more from changes in domestic capital flows, which will be dependent on: 1) lower US rates, and also 2) improved domestic private sector confidence.

Linking to our FX forecasts, we now raise our USD/VND forecasts to 26,500 by 4Q2025, 26,700 by 2Q2026, and 26,900 by end-2026. Our previous forecasts were for USD/VND to rise to around 26,300 before coming off gradually in 2H2026. This forecast change on FX reflects our expectation for higher import needs together with stronger credit growth putting some upward pressure on USD/VND over the next 6 to 12 months.

We also now remove our expectation for SBV to cut rates, even as we continue to expect the Fed to lower rates through 2025 and 2026. We now expect SBV to keep its official policy rate on hold at 4.50% and see 3-month interbank rates staying somewhat elevated near-term above 5%, at least until the longer-term impact of capital market reforms help develop alternative funding sources for Vietnam’s growth.

Over the medium-term, we think that as productivity improvements manifest more in Vietnam, we will likely see inflation come off, the current account surplus improve, even as growth stays around 7-7.5% over the medium-term. We may expect as such the pace of VND weakness to slow to a more reasonable pace as we look beyond the next 2 years, but much will also rest on effectiveness of reform implementation and the key risks of overheating and strong credit growth we mentioned earlier.

As such, we also see the risk of VND weakening more and interest rates rising higher than our current forecast set if there is excessive credit growth and a focus on boosting growth in an unsustainable fashion, raising overheating risks. It is important to highlight that this is not our base case.

Another key risk to watch out for is the upcoming definition of transshipment and how new rules of origin could impact Vietnam’s exports to the US.

Appendix