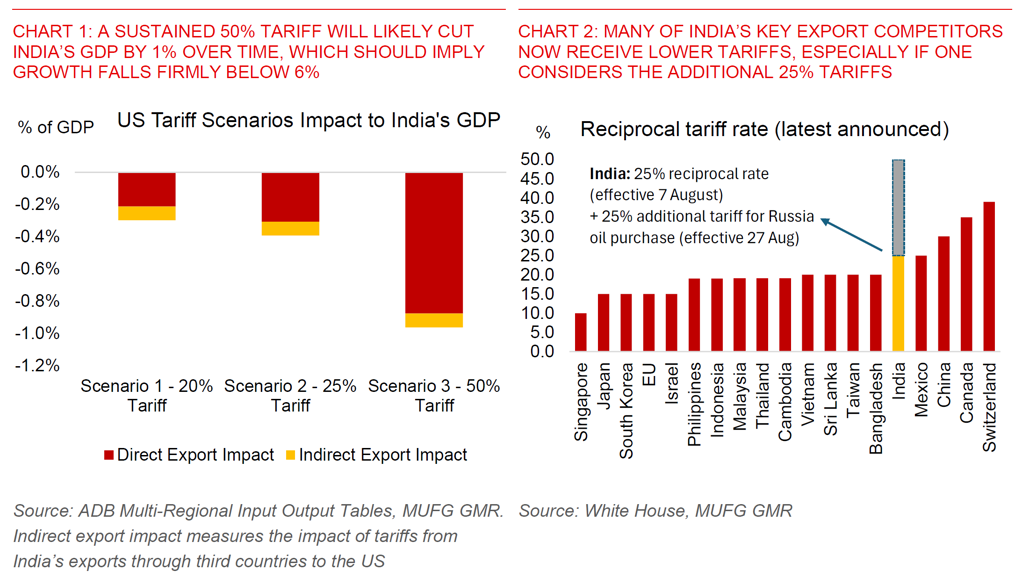

- President Trump recently announced an additional 25% tariff on India for its purchase of Russia oil, effective 27 August. This will be stacked on top of previously announced 25% reciprocal tariffs, but will not apply to exempted products such as electronics and pharmaceuticals which will come under sectoral tariffs later.

- We build on our earlier analysis, and provide additional scenario analysis given the significant uncertainty as to how events could play out from here (see India-US trade talks and tariffs – Delayed and Denied? and 25% additional tariff for India – negative demand or supply shock?)

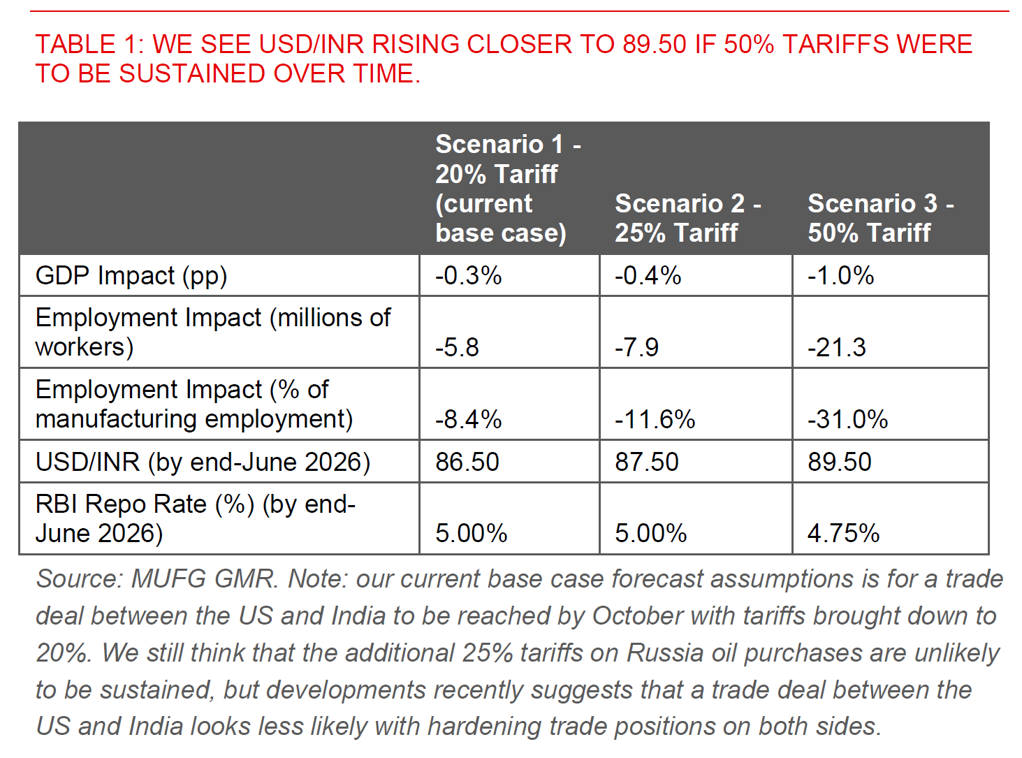

- First, a sustained 50% tariff would cut India’s GDP by 1.0% over time, implying India’s growth falls firmly below 6%yoy through FY2025/26 in such a scenario (see Chart 1 above). Conversely, a 25% tariff could cut India’s GDP growth by around 0.4pp over time, while a 20% tariff lowers growth by 0.3pp as per our sensitivity analysis published earlier.

- Importantly, our numbers imply a more pronounced negative impact to India’s growth as tariffs rise further above 20%. Put differently, we think there is non-linearity to the tariff impact to exports. The key driver is that as tariffs on India rise, the incentive for US importers to substitute to alternative suppliers increases, both because US importers are generally able to do so across many of the products that India exports to the US, and also because tariffs on many of India’s direct export competitors are right now at lower levels (Chart 2 above).

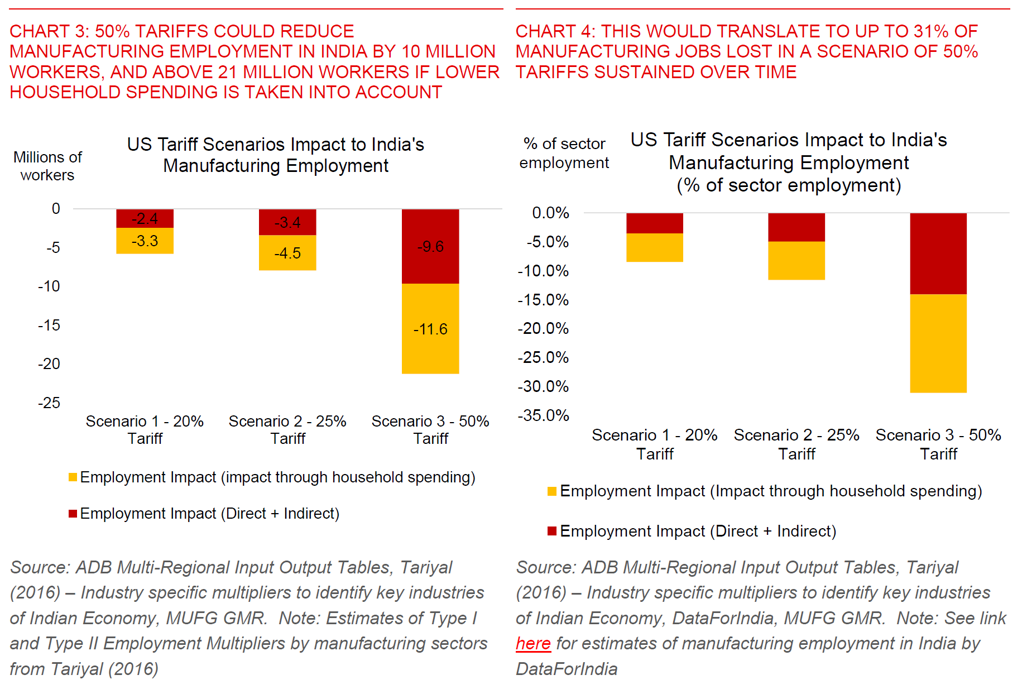

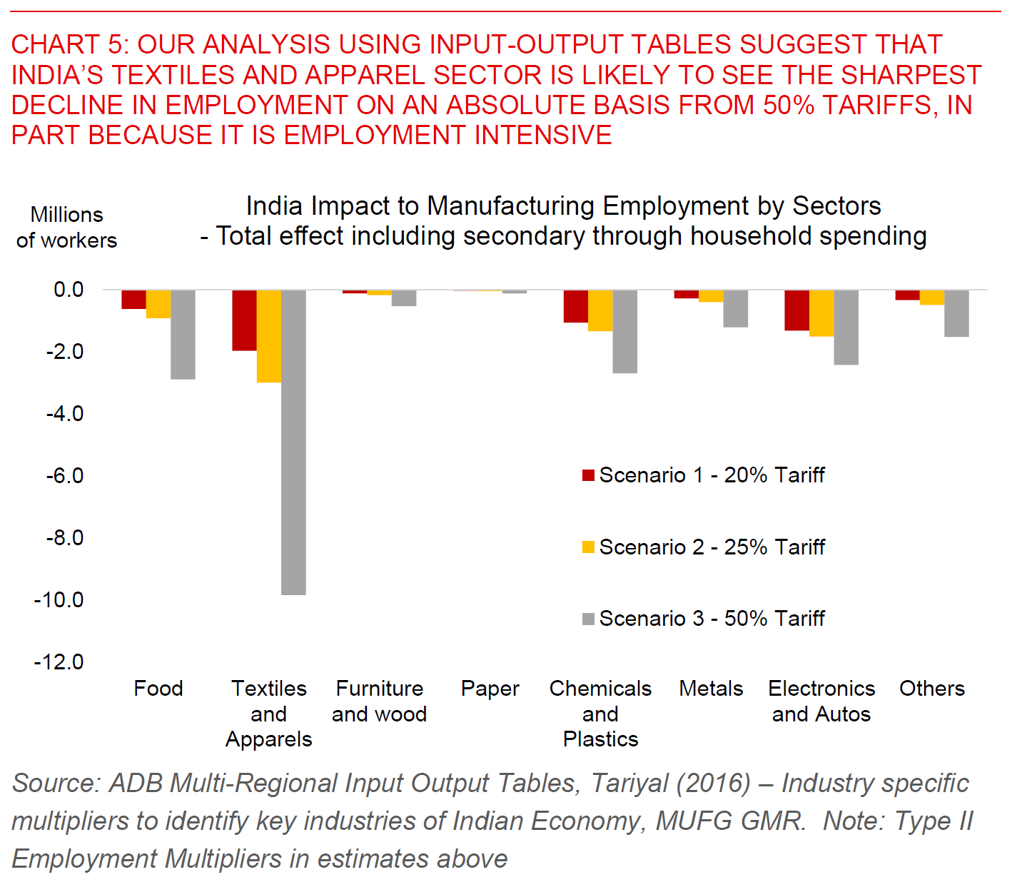

- Second, we find potentially significant negative effects on India’s labour market. A 50% tariff could reduce manufacturing sector employment by 10 million workers over time, and above 21 million workers if we take induced effects through lower household spending into account (Chart 3 above). This would equate to a meaningful 14% of India’s manufacturing employment directly lost and up to 31% on the high end if one includes indirect effects. Many of these workers are very likely also in the informal sector and so social safety nets are correspondingly less robust to begin with.

- The key underlying factor is that the sectors most negatively impacted by high tariffs also happen to be labour intensive ones such as textiles, gems and jewellery, toys manufacturing, food processing, among many others. These are incidentally the very areas that India needs to absorb its burgeoning population into good jobs (see Chart 5). As such, there is also a meaningful distributional and social impact for India beyond just the headline GDP hit.

- Third, we think India’s government will likely take more fiscal and credit-related measures to help exporters and small businesses tide through this difficult period in the near-term, while also increasing spending and cutting taxes to help diversify exports to new markets and shore up India’s domestic demand, especially if tariffs were to stick at 50%. These measures may include interest subsidies on credit for exporters, collateral free loans to small businesses, employment-linked incentive schemes to incentivise companies to preserve jobs, export promotion missions to diversify end-markets, and also rationalise and reduce effective GST rates to boost consumption.

- From a fiscal perspective, we see some chance for India’s FY2025/26 fiscal deficit to slip to 4.6% if 50% tariffs stick. This would be up from an initial target of 4.4%, but importantly still on a fiscal consolidation path from the 4.8% deficit seen last year. What is key for INR bond and currency markets is also whether tax cuts structurally raise the fiscal deficit, or achieves other important objectives such as improving revenue efficiency. We think markets are likely to view fiscal spending that preserves or enhances India’s growth potential positively, even if it may mean some near-term slippage in the fiscal deficit. These may include reducing job market scarring through employment-linked schemes, improving cashflow and credit for exporters and small businesses, and also efforts to diversify export markets beyond the US.

- Overall, we are not making any official changes in our forecasts at this point given the significant uncertainty and different moving parts on tariffs.

- Our base case assumption right now is that India and the US will eventually reach a deal sometime in October to lower tariffs to around 20%. We also view the additional 25% tariffs for India’s purchase of Russia oil as unlikely to be enforced for a prolonged period, especially if we consider alternative scenarios of an eventual resolution in the Russia-Ukraine war as well.

- Nonetheless, developments over the past week suggest to us that a trade deal between the US and India to lower reciprocal tariffs from 25% looks far less likely with hardening trade positions on both sides, even as we think negotiating teams on both sides will continue to speak at a working level.

- If tariffs of 50% were to be sustained, we see USD/INR rising closer to 89.50 levels by June 2026, implying outright INR underperformance against major currency pairs including Asian FX (see Table 1 below).

- With India’s growth also likely to fall below 6% with 50% tariffs, we think RBI will cut rates by 3 more times to 4.75% from 5.50% currently, more than our current forecast of 2 more cuts (5.00%). The central bank is also likely to allow more room for INR weakness to support export competitiveness if it looks clear that 50% tariffs were to be sustained.

- The added complication here is whether global oil prices rise sharply if India (and/or China) materially shifts away from Russia oil purchases towards other sources of oil supply. We have previously noted that the direct impact to India’s current account deficit from the removal of Russia oil discount is manageable at around US$2bn annually, but the indirect effect such as through global oil prices and lower refiners’ margins is much harder to estimate and could be meaningful. We see RBI cutting rates by less if global oil prices were to rise sharply but the bias for INR weakness remains intact in that scenario.

- Over the medium-term, what is far more impactful for India in our view are the potential lost opportunities in terms of future manufacturing FDI arising from the tariffs, beyond the near-term growth hit. While India’s economy should still be supported by its domestic oriented nature and existing deep determinants such as good demographics, the likely slowing in terms of export-related manufacturing FDI implies an even greater pressing need to create alternative growth drivers, and especially employment-intensive ones given India’s burgeoning population.

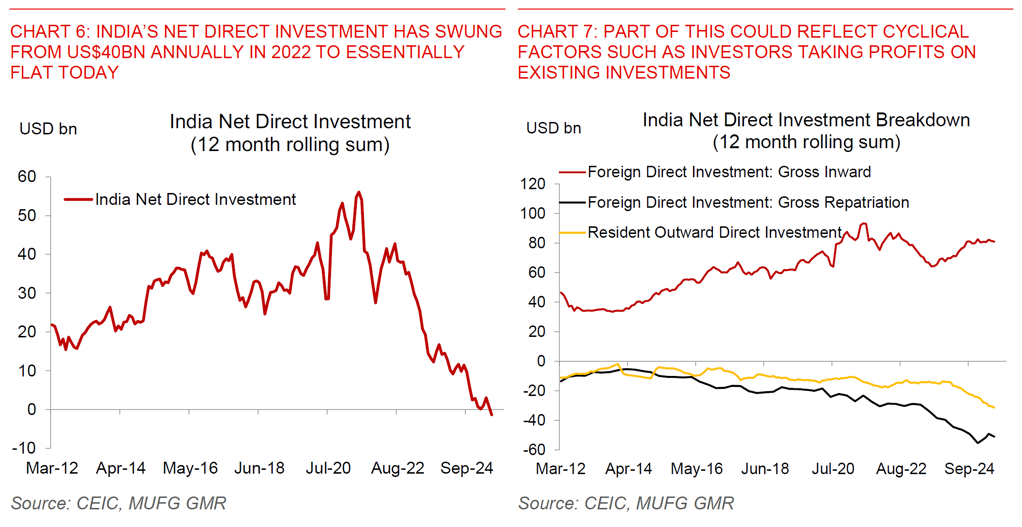

- Linking to a FX perspective, the important change in India’s balance of payments is a sharp decline in Net Direct Investment from around US$40bn annualised in 2022 and essentially flat today – in other words a US$40bn swing in funding of India’s current account deficit (see Chart 6 below).

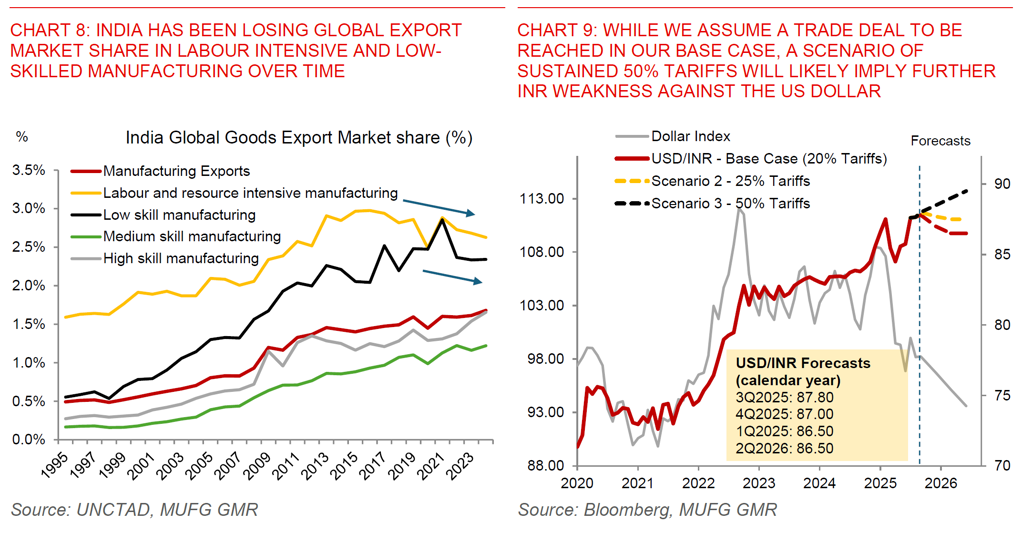

- While some of this swing in net FDI reflects cyclical factors such as investors taking profits on their existing investments (Chart 7) and shifts in the global technology start-up cycle, the evidence shows that India has also been punching below its weight in terms of attracting labour intensive manufacturing FDI compared with the likes of its export competitors such as Vietnam. This is also odd in the context of abundant labour in India and also the fact that many of India’s capital intensive and high-skill intensive sectors such as IT services and pharmaceutical have managed to do very well and compete globally (Chart 8).

- The broader point we are trying to make here is that beyond just restoring growth and rebalancing trade partners as an immediate response to tariff developments, there are many crucial domestic reforms that India can and should do in order to unlock the next wave of private investment and FDI. These binding constraints predate the tariffs and our hope is that the external challenges brought about from tariffs ultimately catalyse a greater impetus for domestic structural reforms in India.