- While we do not know how exactly the Israel-Iran conflict will play out from here, in this report we analyse the channels of Asia’s current account deficits, inflation, and fiscal offsets, to provide a sensitivity analysis of how oil price increases could impact Asia FX markets.

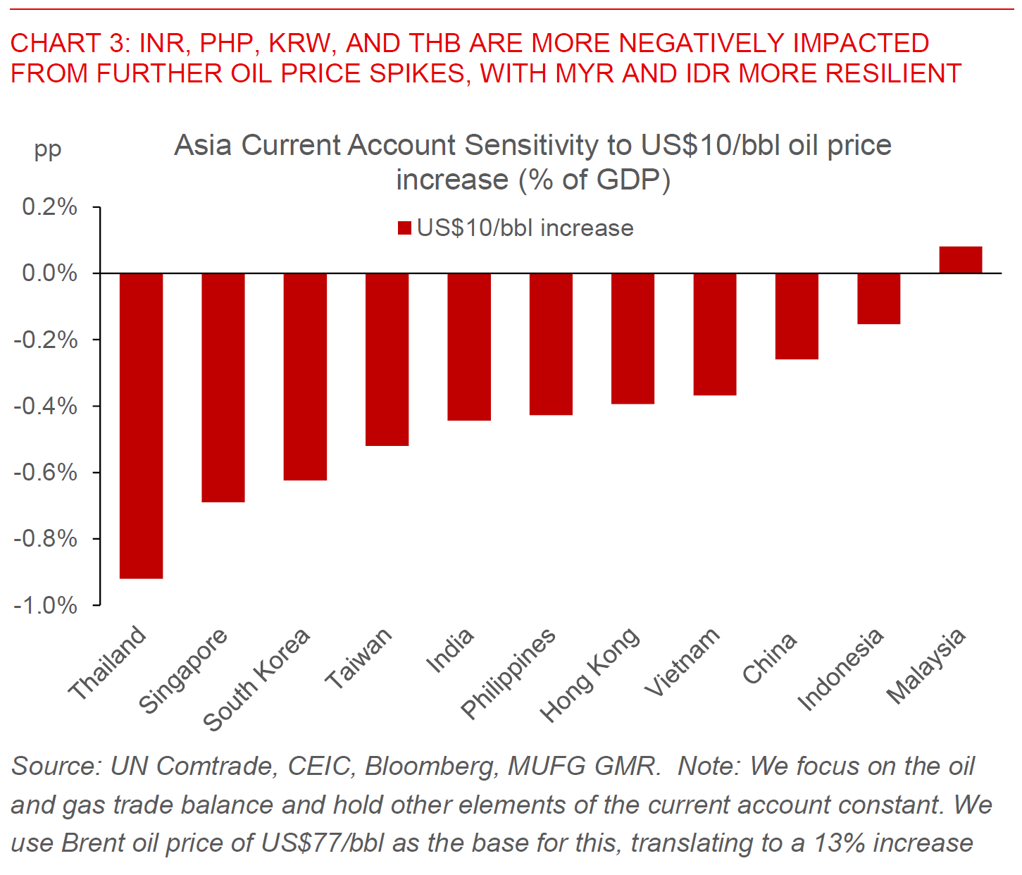

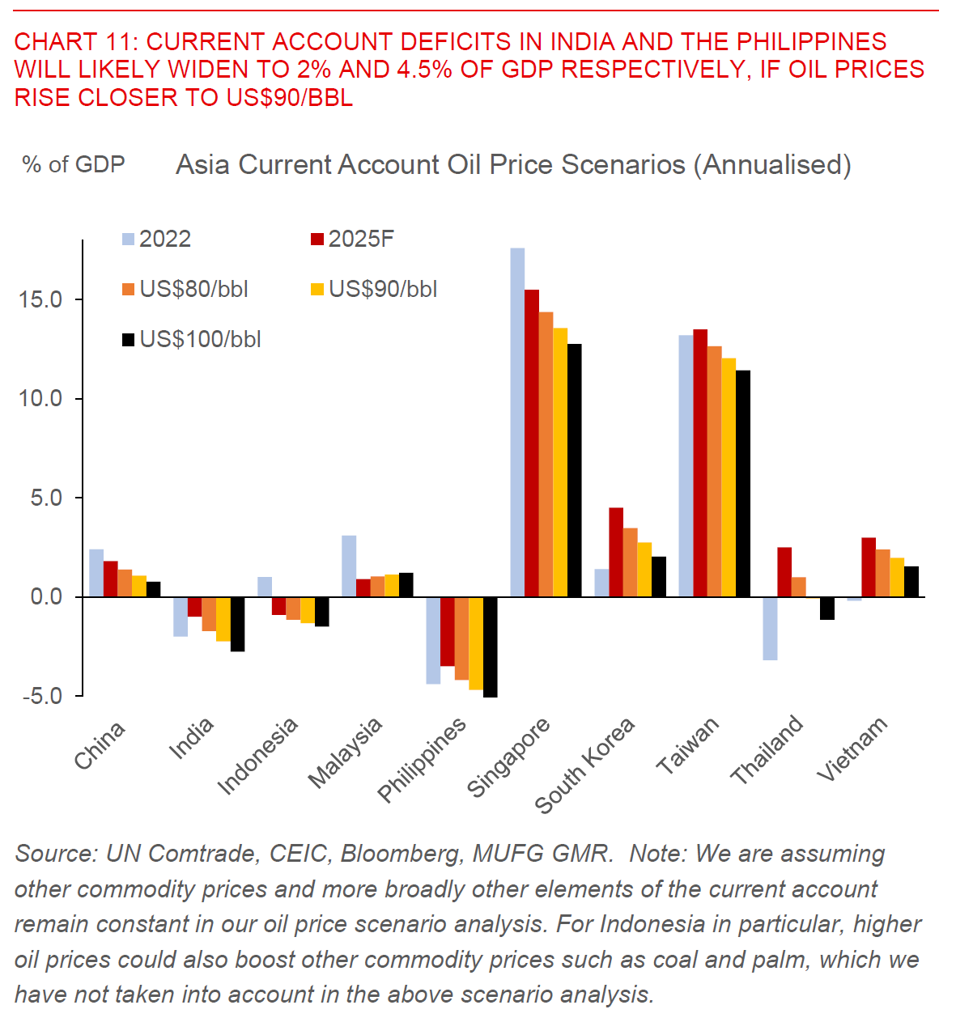

- Our scenario analysis shows that a US$10/bbl oil price increase would reduce Asia’s current account positions by 0.2% to 0.9% of GDP. Specifically, the trade balances of Thailand (-0.9%), Singapore (-0.7%), and South Korea (-0.6%) are the most sensitive to oil price increases, while India and the Philippines will see their current account deficits rise above 2% and 4.5% respectively if oil prices increase unabated towards US$90/bbl.

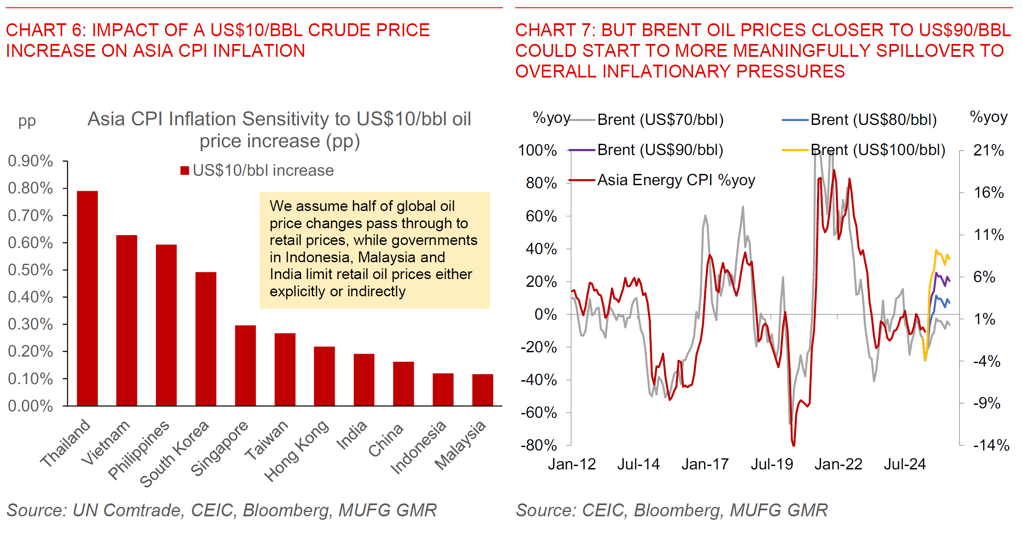

- Looking from an inflation perspective, Asia’s CPI is likely to rise by 0.1pp to 0.8pp for every US$10/bbl oil price increase. Price pressures in Thailand (+0.8%), Vietnam (+0.6%) and the Philippines (+0.6%) are the most sensitive, while Indonesia (+0.1%) and Malaysia (+0.1%) are the least due to our assumption of government subsidies and support to limit the pass through to retail fuel inflation. This could of course change if governments decide to raise domestic subsidised fuel prices meaningfully but is not our base case.

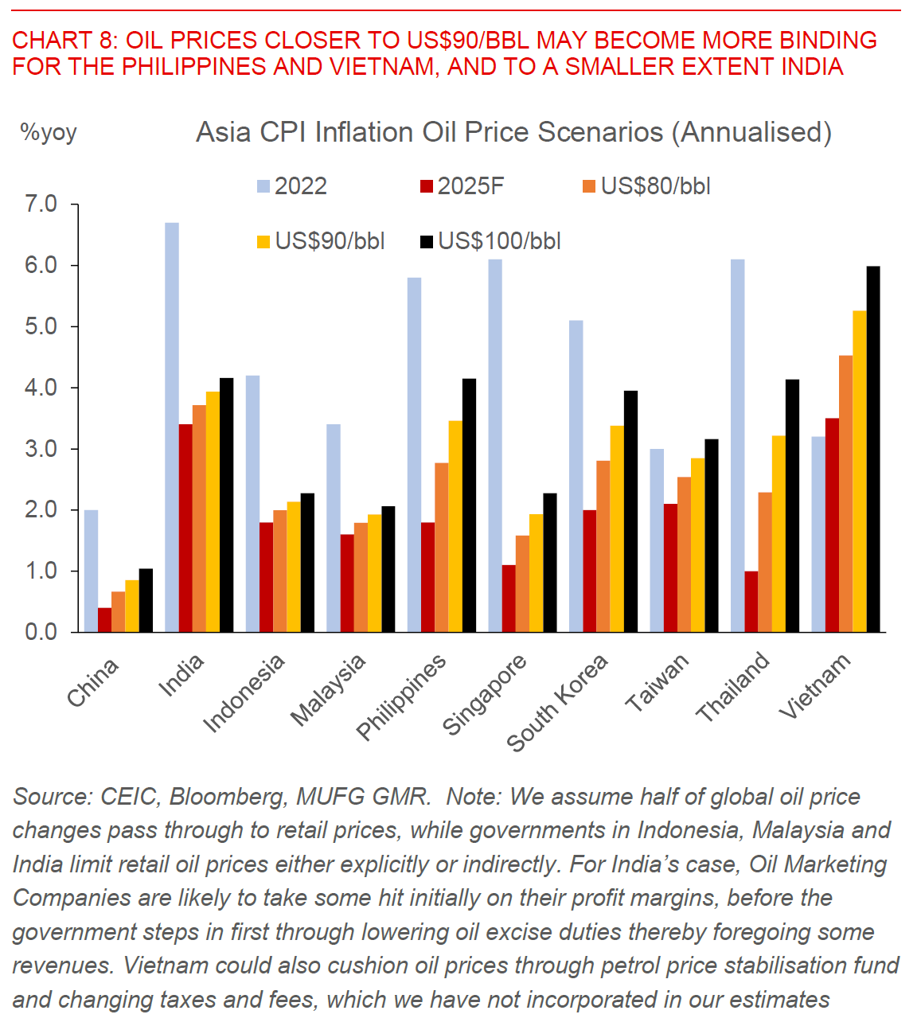

- We think further increases in oil prices could start to impact the policy space of the Philippines and Vietnam, and to a smaller extent India, from cutting policy rates. As we stand however, the rise in oil prices so far should not prevent Asian central banks from cutting rates further to support growth, even if it could delay the timing. For one, the starting levels of inflation and also oil prices across Asia are manageable. Meanwhile, we are in a very different part of the cycle compared to 2022 during the Russia-Ukraine war, with higher oil supply relative to demand, meaningful OPEC+ spare capacity, coupled with the Fed still on a rate cutting cycle (compared with rate hikes back then).

- Putting it all together, our analysis shows that PHP, KRW and THB are more vulnerable in Asia from an FX perspective to further sharp spikes in oil prices. INR is also relatively more vulnerable with a current account deficit closer to 2% of GDP together with relatively higher economic linkages to the Middle East. Meanwhile, the likes of MYR, IDR and TWD should be more resilient. We think the impact on CNY is likely to be minimal.

- Suffice to say, our latest Asia FX and macro forecasts have not taken the geopolitical conflict in the Israel-Iran war and oil prices spikes into account.

- We will likely adjust our FX forecasts for the likes of INR and PHP weaker given this external shock. Nonetheless, given how FX levels in both currencies have already moved weaker, the risks for both currencies could be more two-sided now even as we continue to acknowledge the significant uncertainty in the next steps of the Israel-Iran war. Beyond oil prices, we continue to point to domestic positives such as improving growth prospects and the possibility of a trade deal in India’s case, coupled with the rise in FDI approvals and lower domestic rice prices in the Philippines (see INR – Art of the deal and PHP: steady as she goes).

Israel-Iran war and recent movements of Asia FX

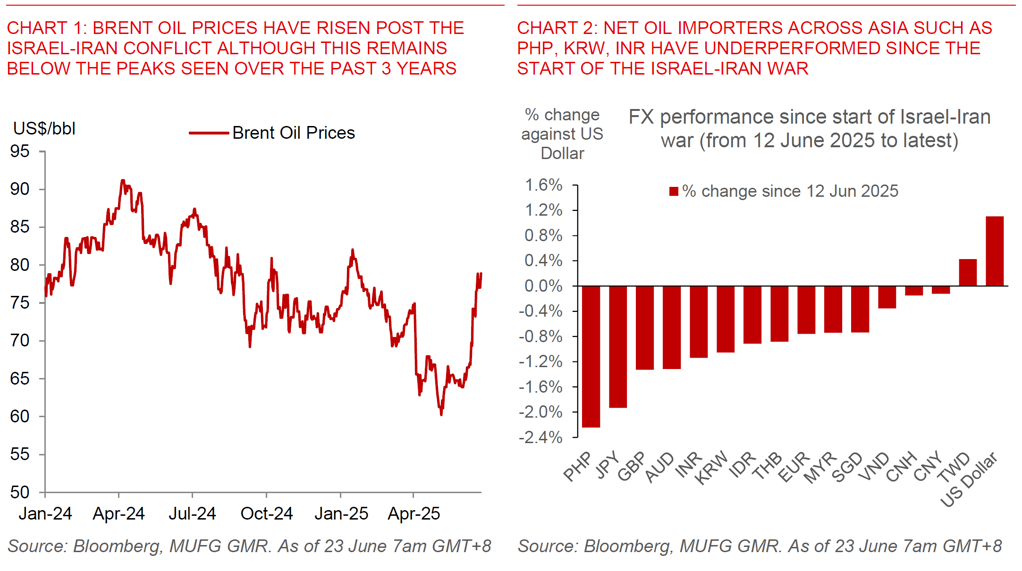

The recent Israel-Iran war started on June 13, and since then Brent crude oil prices have risen from US$67/bbl to US$77/bbl, with a further rise to US$79/bbl at the time of writing following the US military’s bombing of Iran’s nuclear sites. The risk-off sentiment and recent neutral tone of Fed drove a 1% rise in the US Dollar Index. Amidst this background, major Asian currencies had varying degrees of depreciation. The currency with the biggest depreciation was the Philippines Peso which has weakened by 2.2%, while energy and external dependent economies such as the South Korea Won and Japanese Yen have weakened noticeably by 1.1% and 1.9% respectively. Meanwhile, the Indian Rupee has depreciated by 1.1%. Relative less depreciation was seen in others, in particular TWD (+0.4%), CNY (-0.1%) and VND (-0.4%).

The ongoing Israel-Iran war poses upside risks to oil and energy prices, especially if the Strait of Hormuz is disrupted

Moving forward, the degree of potential upside risks to oil prices is dependent on the extent of disruptions to global oil and energy productions and supplies. One key factor is whether the Strait of Hormuz is disrupted – a key chokepoint where a third of all seaborne oil and gas supplies go through. For context, crude oil and condensate transported through the Strait from countries like Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Kuwait, the UAE, and Iran represents about 20% of global oil consumption. In addition, more than one-fifth of the world's LNG supply transits through the Strait, primarily from Qatar.

While it is possible for shipments to be rerouted through alternative pipelines, the extent is overall limited in a scenario of full disruption of the Strait of Hormuz. The IEA estimates that alternative land routes such as Saudi Arabia’s East-West pipeline to the Red Sea and the UAE’s Abu Dhabi Crude Oil Pipeline to Fujairah can offer some help, but their capacity represents barely one quarter of the typical daily volume transiting the Strait of Hormuz. Meanwhile, elevated global oil inventories, OPEC+’s available spare capacity, and US shale production, all could provide some buffer. However, a full closure of the Hormuz Strait would still impact on the accessibility of a major part of this spare production capacity concentrated in the Persian Gulf.

Due to the high uncertainty of the outcomes and duration of this war, we try to give a scenario and sensitivity analysis on how a US$10 rise in Brent oil prices will affect Asian economies and FX through various channels.

Three main channels from oil price shock to Asia FX – current account deficits, inflation, fiscal

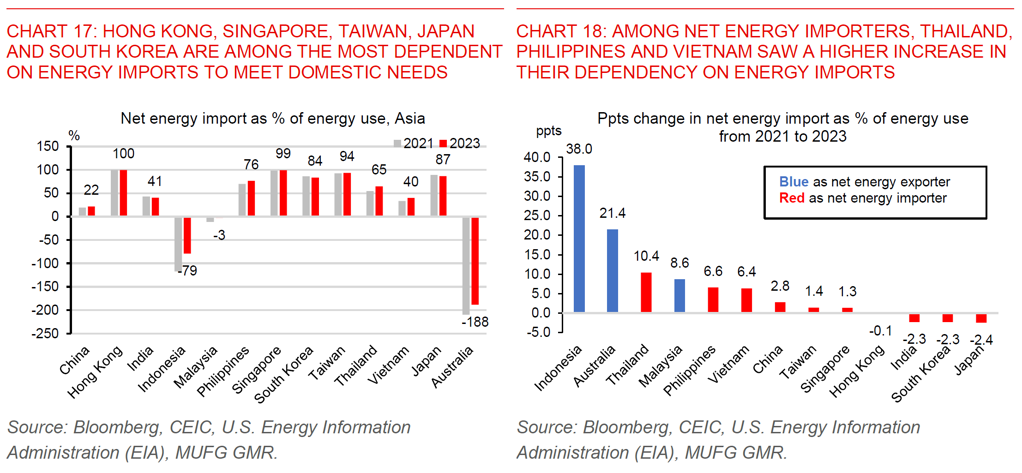

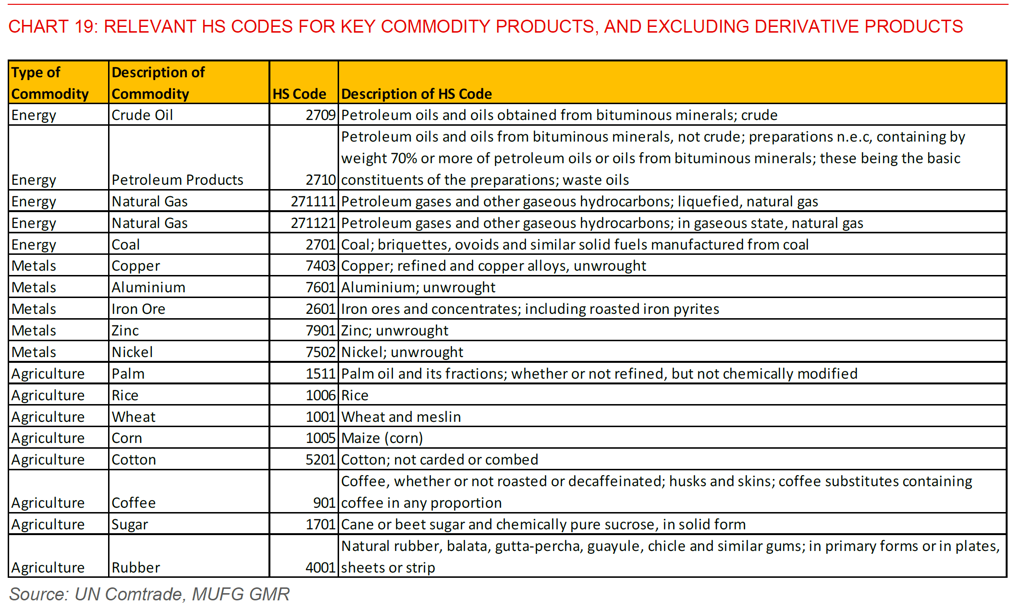

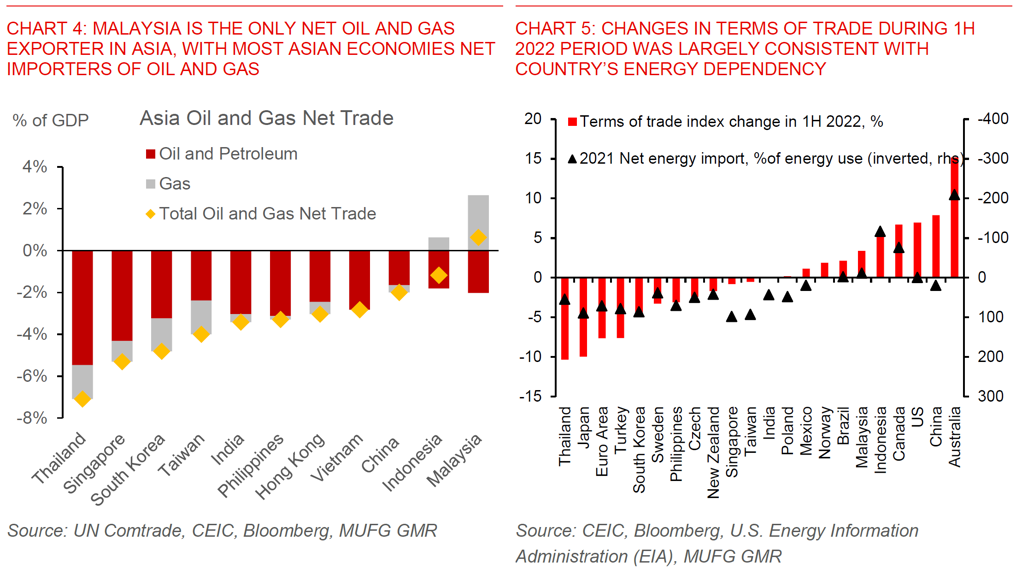

Asia is a big net oil/energy importer, particularly for countries like Thailand, South Korea, Philippines and India. As such, an oil price shock would create a real negative impact on most Asian economies. For Asia FX, an oil price shock would change individual economy’s terms of trade, trade balance, current account balances, inflation, and monetary policy, all of which will feed through to FX.

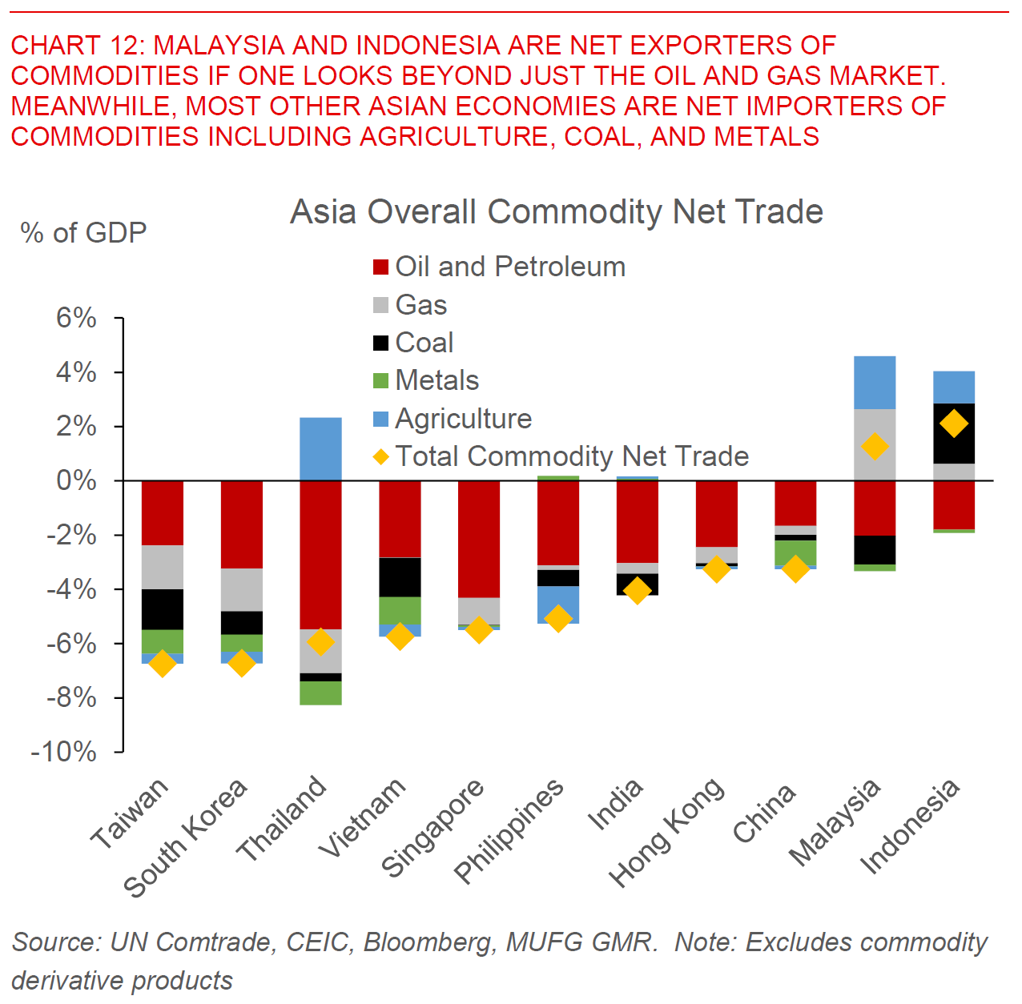

Overall, our calculation indicates that a US$10/bbl rise in crude oil price could worsen Asia’s current account by 0.2-0.9% of GDP (see Chart 3 below). Thailand, Singapore, and South Korea are the most sensitive, while Malaysia and Indonesia are likely the least impacted, with Malaysia in particular the only net oil and gas exporter in our region (see Chart 4 below).

Meanwhile, current account deficits for the Philippines and India could widen above 4.5% and 2% of GDP respectively if oil prices were to rise above US$90/bbl on a sustained basis (see Chart 11 below).

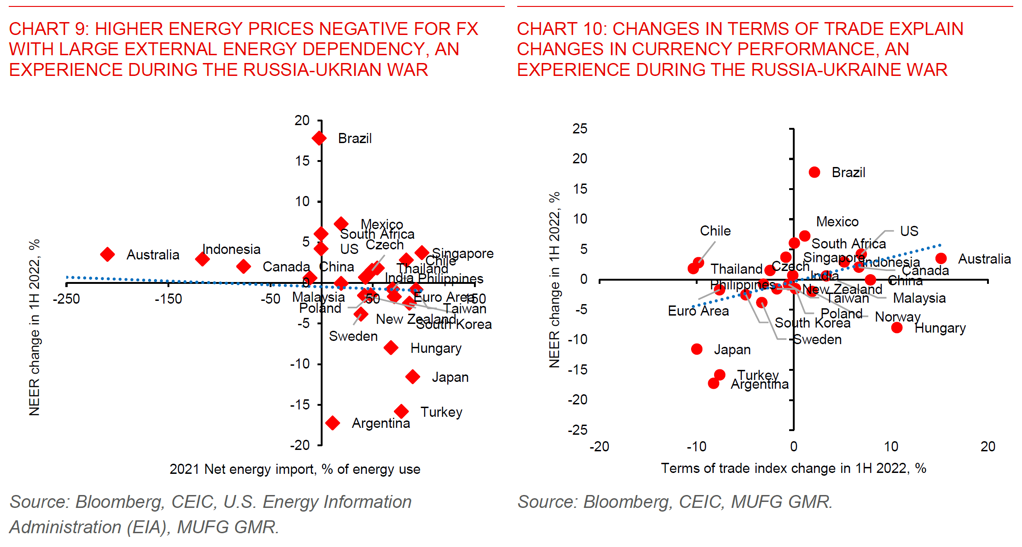

External energy dependency and associated terms of trade condition changes are main reasons behind the current account changes, due to an oil price shock. The experience of Russia-Ukraine war in 2022 sheds some light on the trade dynamics and FX path ahead. On 24 February 2022, Russia launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and crude oil price surged significantly in 1H of the year with Brent crude oil price rising from USD 78/bbl to USD 115/bbl, for an approximate gain of 48%. Other energy prices like natural gas and coal also rose during the period. In the meantime, we saw significant shift in terms of trade indicator among countries during 1H 2022, and that pattern of shift was generally consistent with whether the countries have significant net energy importing or exporting positions. For instance, we saw net energy importers’ ToT worsened such as Thailand (-10.3%), Japan (-10.0%), Euro area (-7.6%) whereas ToT improved for net energy exporters like Australia (15.2%), Canada (6.7%) and Indonesia (5.2%).

Of course history often rhymes but never repeats, and the oil supply and macro dynamics now are quite different from what we saw during 2021-2022 with COVID and significant fiscal stimulus being key elements of the cycle back in 2022.

A sharper rise in crude oil price towards US$90/bbl could constrain some Asian central banks’ from cutting rates

Beyond current account deficits, we think Asian central banks across the region likely remain on track to cut policy rates further at current oil price and inflation profiles, although some may delay the timing of cuts. If oil prices start to rise closer to US$90/bbl, it could be more binding on central banks across the region.

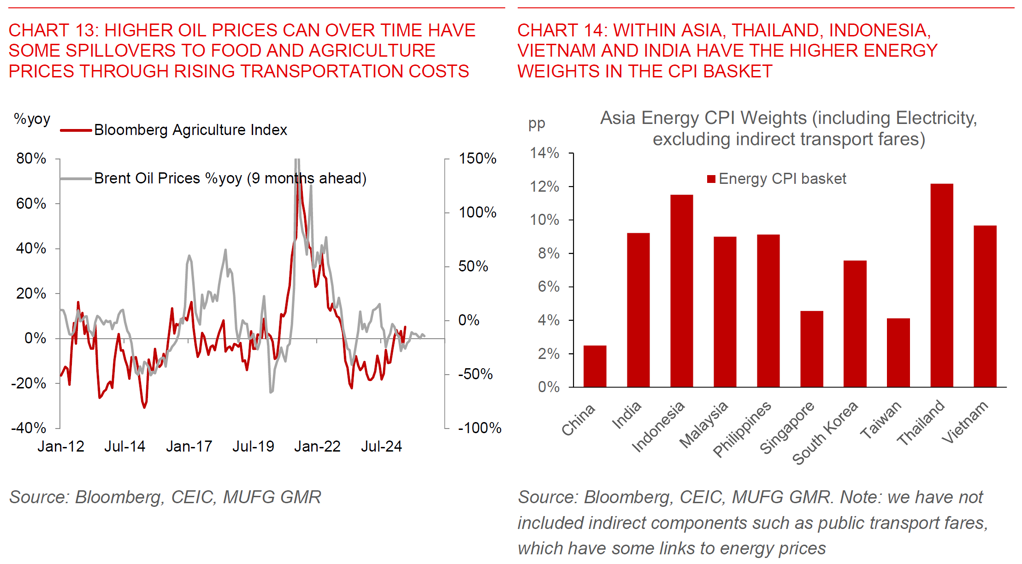

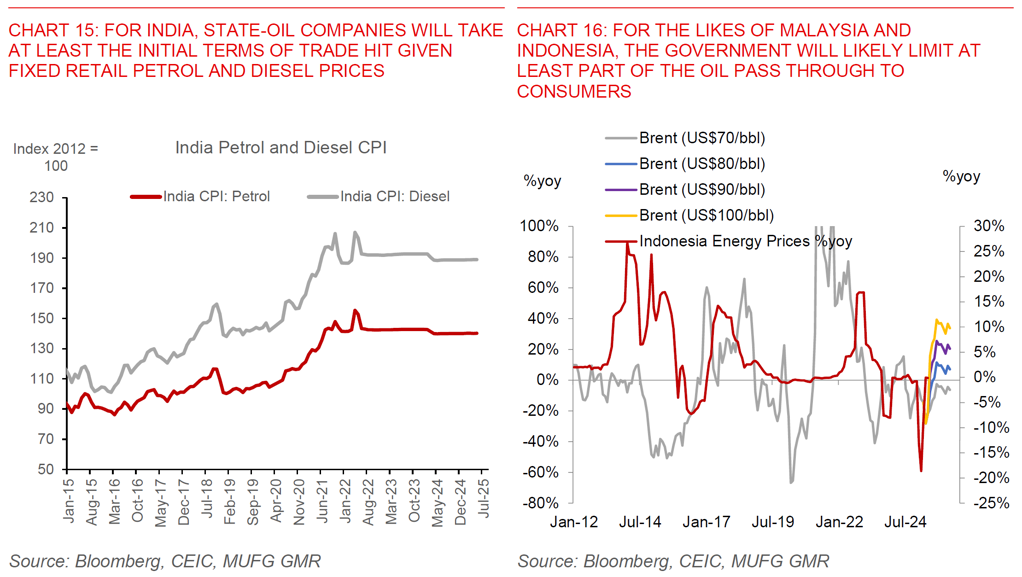

Our sensitivity analysis shows that a US$10/bbl increase in oil prices would raise inflation by 0.1% to 0.8% across Asia, with China the least impacted and Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines more on a relative perspective. For some countries such as India, Indonesia and Malaysia, fiscal authorities and state-owned oil companies will take the hit and limit the pass-through to retail price inflation at least initially, although the cost will still have to be borne by fiscal authorities either explicitly or implicitly. For others such as the Philippines and Vietnam, the pace of FX depreciation may be a binding constraint here to further rate cuts. If oil prices were to rise to US$90/bbl, we think this could start to impact the policy space of the Philippines and Vietnam, and to a smaller extent India, from cutting rates. That said, we think both central banks will retain a dovish bias assuming oil prices do not rise sharply from here.

PHP, KRW and THB likely more impacted, followed by INR due to its current account deficit

Currency value has a clear positive relationship with terms of trade condition, a negative relationship condition with energy dependency. When measuring nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) performance over 1H 2022 across 26 countries we tracked, we found a positive correlation between the change in countries’ ToT and their NEER performance over the period. That positive correlation supports the theory that an increase in terms of trade would strengthen a currency, and conversely a decrease in terms of trade would weaken a currency.

Our analysis suggests that PHP, KRW and THB are likely to be more negatively impacted by further sharp spikes in oil prices. INR is also more vulnerable due to its current account deficit and relatively higher linkages to Middle East

For PHP, although the Philippines’ current account deficit sensitivity to oil price increase is not as high as the likes of Thailand and South Korea, the relatively large starting levels of the current account deficit at 3.5% of GDP makes the currency more vulnerable due to greater external financing needs. While we had been sanguine on the prospects for PHP due to a combination of manageable inflation helped by lower oil and domestic rice prices, and as FDI approvals start to be implemented, significant oil price spikes driven by geopolitical tensions changes a meaningful part of our existing thesis. Our forecasts for USD/PHP to head towards 54.50 levels by 4Q2025 are at risk if oil price spikes and geopolitical risk premia prove lasting. Nonetheless, with USD/PHP already spiking as quickly as it has, the risks for PHP may be more two-sided at current levels, even as we highlight the significant uncertainty on the Israel-Iran conflict and remain cognisant on the left-tail risks on oil prices in particular (see PHP: steady as she goes).

KRW is generally seen as a currency sensitive towards global oil price changes, due to South Korea’s high energy dependency. More specifically, South Korea relies on Middle East for a significant 70% of crude oil imports in 2024, and the dependency on the region had increased since 2021, when it accounted for 59% of crude oil imports. We estimate a potential more than 0.6% current account /GDP decline for a US$10/bbl increase in oil price. In addition, we are also concerned about the oil price changes pass through to the final consumers, which may further dampen their willingness to spend amidst sluggish domestic demand. Combined with weak overall economic fundamentals, KRW is likely to be among the top two currencies most negatively impacted specifically to oil price spikes.

For INR, the current account deficit is currently manageable at 1% of GDP. Nonetheless, with every US$10/bbl increase in oil prices increasing India’s CA deficit by 0.4% of GDP, substantial oil price spikes could start to constrain policy space to support the economy not just by RBI but to some extent from a fiscal perspective. India’s current account deficit will likely rise above 2% of GDP if oil prices were to spike to US$90/bbl. For India specifically, part of the negative terms of trade shock will be borne at least initially by lower profit margins from Oil Marketing Companies given fixed retail gasoline and diesel prices. If oil prices were to rise more clearly above US$85/bbl, we may need to see more fiscal support from authorities to compensate oil companies, although we note that this could come at least initially through foregone revenue from the government lowering oil excise duties. We have been expecting USD/INR to head lower towards the 84.00 levels by 4Q2025 with a combination of an expected trade deal, manageable inflation, a pickup in growth and better external inflows (see INR – Art of the deal). Higher oil prices if lasting changes at least part of our thesis on INR, and we would likely revise our USD/INR forecast profile higher if geopolitical risks remain elevated moving forward. Nonetheless, given the weakness already seen in INR, the balance of risks for the currency could be more two-sided notwithstanding the significant uncertainty in gauging the next steps forward for the Israel-Iran war.

For THB, it remains highly sensitive to oil price shocks, where a $10/bbl increase in oil prices is estimated to reduce the current account balance by 1.1 percentage points of GDP — the largest negative impact in Asia. However, Thailand’s improved external position could provide some cushion. The current account recorded a surplus of 2.0% of GDP in 2024, largely driven by a strong rebound in tourism. This marks a stark contrast to 2022, during the Ukraine-Russia war, when the current account was in a deficit of 3.5% of GDP due to the Covid-induced hit to the tourism sector.

For TWD and CNY, we think the drag from a worsened current account positions on the currencies are limited. While Taiwan’s energy dependency is also high and as such is expected to reduce the current account balance by 0.5ppts of GDP for a US$10/bbl increase in oil prices, it has a healthy level of current account surplus (14.3% of GDP) to absorb the shock. In addition, its economic fundamental remains sound with strong AI demand means its current account is unlikely to deteriorate much despite some slowdown in exports in 2H is likely as front-loading shipment fades. For China, it has a relatively low energy dependency compared to other net energy importers, which translates into a lower impact of -0.3ppts to its current account balance for a US$10/bbl increase in oil prices. As such, we only see a mild upside risk to our USD/CNY forecast on this front.

Conversely within Asia, we think MYR, and to a smaller extent IDR, should be relatively less impacted directly from higher oil prices. For Malaysia in particular, it is the only market in our region which will see positive terms of trade impact from higher oil prices, given its status as a net oil and gas exporter (albeit small at 0.6% of GDP). The net impact to Malaysia’s economy is more complex than headline numbers suggest however, given that it still does subsidises some oil prices such as Ron 95, even as oil revenues including from Petronas dividends should at least partially help offset that on the fiscal books. While the Malaysia government has been talking about removing fuel subsidies for some time, sharp oil price spikes may delay these reforms in the near-term given the possible negative impact to consumer sentiment.

IDR is an interesting case here in Asia. Indonesia is a net oil and gas importer to the tune of 1.2% of GDP. However, if one includes other commodities such as palm, coal, and other metals, Indonesia’s net commodity trade position amounts to +2% of GDP (see Chart 12 in Appendix). We note that higher oil prices tend to correlate quite well with food prices due to higher transportation costs, and to some extent above a certain threshold could also spillover to alternative fuels such as coal. Net-net, we think the extent that commodity prices rise more generally including spilling over to palm oil and coal prices may provide a partial offset for IDR. We also believe the government will be reluctant to raise domestic fuel prices amid slowing economic growth. Even if fuel prices are adjusted, we do not expect a full passthrough of higher global oil prices to consumer prices

Appendix

Possible scenarios for the Israel-Iran War:

There are of course many shades of grey in terms of scenarios for the Israel-Iran war, and it’s important to stress our base case forecasts do not assume a full Strait of Hormuz disruption which we view as unlikely for now.

Our G10 FX research team had earlier mentioned several scenarios to be cognisant of, including (see USD downside risks persist in most Middle East scenarios):

#1: De-escalation and an Iran nuclear deal

#2: Current status quo continues

#3: Escalation and possible US military involvement and/or Iranian retaliation

#4: Significant escalation with possible regime change, and more aggressive response from all sides including Iran.

With the recent involvement of the US military, the focus now shifts to how Iran responds and retaliates, and the extent of possible oil supply disruptions. From a markets perspective, the last scenario of significant escalation may be the most disruptive, with highest probability of a full Strait-of-Hormuz closure.

While we have not officially revised our Asia FX forecasts post the Israel-Iran war and consequent oil price spikes, we currently implicitly assume that there will not be significant physical oil supply disruption, with managed escalation as a reasonable base case assumption for now.